– ISLAMABAD –

The story starts with smoke, curling and twisting in the air, in a dingy lime green hotel room that, like the rest of this country, seems eternally stuck in the seventies. A soap opera chatters away on a flatscreen on the wall, as the underpowered ceiling fan makes little attempt to clear the room of the haze. Sitting in stoned silence, cross-legged on the side of the bed, I watch the smoke twirl while my new friend crumbles bits of Afghan hash into an excavated cigarette.

Getting off the plane in Islamabad was like a bullet being loaded into a chamber and fired with explosive force. At first, everything felt surprisingly normal as I walked the white marble floors into arrivals. Now here I am, a couple hours later, swilling chai and hotboxing a seedy hotel room with someone I just met.

“Are you… relaxed?” Feroz asks me with a devilish grin. I am, the hash went straight to my head. And though my friend keeps asking if I’m feeling okay, I still haven’t figured out if he’s just planning to kill or extort me in some way.

Feroz is a taxi driver, hash peddler, solicitor of disreputable women, and an overall fixer: he knows everyone, all the cops and the airport authorities, and anything one might want – be it a weekend getaway or illicit vodka – he can make happen, at a price.

The muezzin sputters from a nearby mosque calling the faithful to prayer. I ask Feroz if it’s the time for fajr, but already know that it is. He nods but doesn’t look up from his task. The streets of Islamabad are still dark; no soul seems to stir save for the odd dog or cat.

Feroz finishes off the joint, anointing it with a few strokes of chai from the bottom of his cup. As I inhale, I think how surreal this seems, like a scene straight out of some Victorian orientalist’s wet dreams. But it’s really just a scene from my own.

Feroz smiles, his huge moustache fanning out to reveal yellow, rotten teeth.

“You are foreigner,” he says. “But I feel this is your country.”

– GILGIT –

I didn’t travel to Pakistan to get stoned on hash, although that was one of my secondary or tertiary goals. I came here to ride my bike through the Karakoram Mountains, the western extension of the Himalayas, and home to such unprominent peaks as K2, Gasherbrum and Broad Peak.

Before I left, a lot of people asked, “Why Pakistan?” Most people I talked to didn’t know much about the country and had never thought of it as a travel destination. Let’s face it, most people thought of it as a hotbed of terrorism and great place to get yourself killed, so why go there? I’d been drawn to Pakistan for a long time and it was difficult to explain the fascination: whether it was the mystical Sufis or gun-toting militants; big mountains; the pomp and regality of Pakistani culture or even the bad seventies pastiche, there was no single reason that made me want to go – it was all of it.

The starting point for my bikepacking journey is the regional hub of Gilgit, a drab and sprawling city occupying a wide swathe of the Indus Valley. So here I am, dragging my bike bag through the rutted streets as inquisitive children and animals look on.

Feroz didn’t kill me after all, he really just wanted a buddy to smoke with. So a hop, skip, and momentary freefall over the foothills of the Karakoram, and I arrived at Gilgit airport early this morning.

Fortunately my accommodations aren’t far from the airport. I check in to the Park Hotel. International inclusiveness is assured by the array of banknotes pasted across the desk. Security is assured by the sawed-off shotgun propped up behind it.

The first step is to unpack and assemble my trusty Ogre, ensuring my bike bag with the hotel for the next two-ish weeks. I poke my finger at a date on the calendar and shrug, then wave it around erratically to indicate that I don’t know when I’ll be back – just don’t throw it out, okay?

After a foray to gather the last few supplies, I sit down to dine, my chicken biryani and I occupying the Park Hotel dining room singlehanded. I dig into the enormous pile, expecting to savor what is one of my favorite dishes, when I’m treated to a different Pakistani delicacy – dining in darkness. A routine power outage has struck. Staff appear to drag back curtains, the late day sun having to suffice.

– JAGLOT –

On the outskirts of Gilgit, I pause to admire Rakaposhi and cue up my playlist. Mission of Burma has been my jam recently, so I thumb through albums and put on Peking Spring for the forty kilometer ride to Jaglot. It feels surreal to be heading out on a decade-long dream, and a slamming soundtrack accompanying the adventure goes without saying.

Over the next few days, it’s my plan to reach Skardu, a small city that is the traditional jumping-off point for expeditions to K2. Instead of taking the regular road to get there, I intend to take a circuitous route across the Deosai Plains.

To say Pakistan is unknown among bicycle tourists would be a lie. The deservedly popular thing to do is ride from Islamabad to China on the Karakoram Highway. But the popularity of said route is the exact reason for my aversion to it. I aspired to pedal across the vast expanse of the Deosai Plains and ultimately reach the mythical (to me) village of Hushe. Thus, these are the only kilometers I’ll spend on the Karakoram Highway, riding south to Jaglot, then chugging east into Astor valley.

As I arrive on the edge of Jaglot I start looking for somewhere to buy a drink. The ride here from Gilgit was characterized by a beautiful kind of desolation made of unending brown moraine. Its very appearance dried me to the bone.

Parking my bike outside the convenience store and walking inside, I experience my first taste of the unique social phenomenon that comes with being a white guy on a bike – or any foreigner, really – in Pakistan. That is, you are the social phenomenon!

One by one the locals appear. First, just two of them. Then two more. Then two more. Then two more. All of them just standing there peaceably in their pajamas, staring at me, chewing their naswar and asking stilted questions: “Who are you?” “Where are you going?” “What is your country?” “Are you married?” “Why not?” The list goes on. Somebody brings me ice cream; I’m chuffed and say salaams with my hand on my heart.

On the outskirts of Jaglot, I stop and arrange to sleep at Salman Guesthouse, a modest homestead offering my first view of Nanga Parbat, one of the Karakoram’s eight thousand meter giants.

I venture off to roll a cigarette and soak my feet in the icy blue creek. A nearby boulder is the bastion of an army of boys, leaping and shouting and launching themselves into the drink. I’m joined by a trio who come to scrub their shalwars and proceed to ogle everything about me: my bike, my watch, my phone, even my shades. About each, they want to know one thing – how much? I decline to inform them that the combined total of these items would equal to them a small fortune.

– ASTORE –

I’m up before anyone else at Salman Guesthouse, tip-toeing over trays from last night’s chicken karahi and packing my bike out in the yard. The ride out of Jaglot is particularly pleasant, the cool morning a precursor to the oppressive heat to come.

At the Nanga Parbat viewpoint I stop to take a picture, and no sooner do I dismount my bike than I find myself whisked away by two affable Lahoris with invitations for tea and hash. Conversation is batted about their hotel room as they pack and prepare to head to Deosai on their motorbikes. Despite their lateness, calls come for one or two more joints from one camp, inciting protests from the other. They look to me to solve the quarrel but – I don’t object!

I descend and cross the Indus River, then wind my way through the chasm that leads to Astor. The sun is perched defiantly above the canyon walls, which radiate heat into the center of my skull like a microwave. Sweat drips off my face, splashing all over the cockpit of my bike as I negotiate each switchback, telling myself that what I’m doing isn’t as difficult or dangerous as it seems.

At the top I relax a little, but still am careful of huge rocks littering the road and a massive drop down the river beside me. A speeding white Landcruiser appears in a cloud of dust behind me, so I swerve to the side as it skids to a halt.

“Too hodt, too hodt!” exclaims the driver. I can’t tell if he’s saying “too hard” or “too hot”, but either statement is entirely accurate at the moment.

“Too hodt,” he repeats, indicating I should put my bike in his truck and get inside.

“No, no!” I politely refuse. Riding up this canyon has positively sucked, but accepting a ride goes against my principl–

“Too hodt,” he reiterates as he and his brother start manhandling my rig into the back of the vehicle. I’m still standing there vociferating about “principles” with a beet-red face when I’m forced to admit defeat.

“It is too fucking hodt,” I say and hop in the air-conditioned truck.

Kash and his brother are from Astor and returning from Swat with a new vehicle. I expected to find a hotel when I got to Astor but that is now unnecessary. Arriving at Kash’s home, I’m shown to the bathroom and invited to wash. After a shower, I sit down to platter of palau. Of course, it’s expected that I’ll sleep there that night.

Kash lives with his brother, nephew, and a handful of women, the exact number I am not sure. Everybody lives in a green, one storey house with a guestroom accessed from outside, and a large garden in the back overlooked by the mountains around Astor. Kash’s nephew, Hiram, is an engineering student in Karachi and we’re left to strike up a conversation that lasts for a couple of hours.

After dinner, Hiram looks at me sleepily. We’ve been chatting all afternoon, comparing cultural notes, tooling around Astor, and after gorging ourselves on an elaborate feast prepared by his family, we’re both exhausted.

“Tomorrow, what is your plan?” he asks.

“I’m going to Deosai,” I say. I know Hiram has appreciated my presence here. I’ve been more than a novelty, I’ve become a real friend. I suspect he’ll be let down by me leaving so soon.

“In my opinion, you will not go to Deosai by cycle,” he says, and I ask him why he thinks so. This is the low season, he says, the weather is unpredictable. The plains are deserted this time of year. Plus there are man-eating bears. I know Hiram wants to persuade me to stay in Astor, but part of me wonders whether I should listen to him. The truth is, I don’t know if it’s possible to ride a bike across Deosai or not. I haven’t heard of anyone trying and I don’t know if it’s been done before.

“Hiram, I have to at least try,” I say. “I can’t come all this way and not try.”

In the morning, I’m getting saddled on the street while the guys hang out waiting to say salaams. Hiram’s mum waved to me from the window as I hoisted my bike up the stairs, what a sweetheart! These people treated me like more than a guest, I feel like I’m saying goodbye to by adopted Pakistani family.

I shake everyone’s hand and lastly give Hiram a hug. I wish I could stay longer but I’m on a mission to get to Deosai.

– DEOSAI –

The first drops of rain strike as I approach the army post at Chillam. These guys are trained to take on Indian soldiers but a white dude on a bicycle has them all looking spooked.

“I’m going to Deosai,” I tell them as they hand around my passport with grave looks. With a sullen nod the gate is lifted and I’m directed up the road to find a hotel and chow.

Ravi stands at the entrance of his diner-cum-hotel, smoking a cigarette with one hand on his hip splaying the tweed sportcoat that marks him as a man of the business class. He’s the “manager”, he tells me, smiling proudly as we walk inside, but his friends plunk him in a chair and announce he’s “just a waiter” in a roar of laughter.

Ravi’s restaurant is little more than a squalid dive servicing the procession of Landcruisers plumbing Deosai in the summer, or the occasional truck driver making runs to or from Skardu. His establishment boasts no lighting nor makes attempts at cleanliness of any kind. It simply sports a few plastic tables and a row of divans where two spindly, shawled figures natter amongst themselves and puff away on cigarettes in the dark. I drag a chair over to where daal and karahi are placed and devour them, leaving only the sauce on my fingers to lap clean as well.

The next day heralds my ascent to the sanctuary of Deosai. I wake up on a dirty mattress and brush my teeth in a dirty sink and scarf down breakfast of oily eggs and paratha in my room before setting out to cycle up the hill.

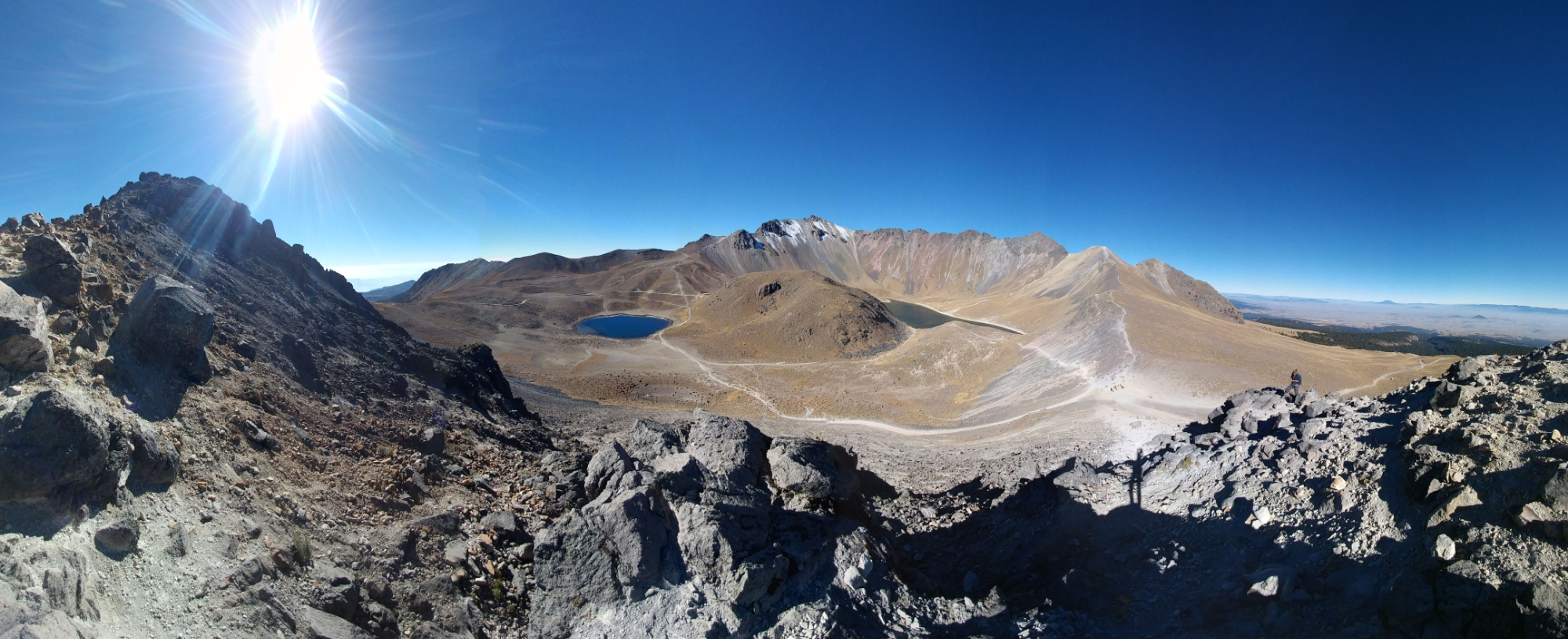

I climb high into the surrounding pastures as a delerious grin adorns my face. Pavement turns to gravel as the road snakes around the contours of the mountainside, over a pass and out of sight. When I reach the top of the pass, a vast, rolling green tableland opens up before me, ringed with distant silver peaks. I pedal along in astonishment as shimmering Sheosar Lake appears to complete the view.

This is the highlight of my life, tires rolling smoothly through the fine brown dust, splashing through streambeds, the sun scorching to little effect in the cool, dry, high altitude air. I’ve even got a little hash tucked in my framebag for a time like this. I stand there coughing, my head abuzz, alone for kilometers and surrounded by wilderness as far as the eye can see. I can only laugh – I can’t believe I made it here.

A rocky descent rattles me and my bike as the orange glow of the afternoon sun floods the basin where, at the bottom, a tiny collection of tents is located. Barapani is the second and wider of two rivers traversing Deosai, hence the name of the river (“big water”) and campsite adjoining it. In summer, a cook tent is set up here by locals to serve food to passing tourists, and I’m in luck that one’s still open.

I take a bowl and stand in line to be served in the musty tent. At a long table a menagerie of Muslim men mow into their meals. I reach the front of the line and a ladle of slop is distributed in my bowl by the cook. “More?” he says, as though wondering why I’m still standing there, but I go and take a seat at the table.

Dinner is followed by hash with new friends as the sun sets on the great Deosai Plains. We sit in the vestibule of my tent rolling joints and laughing until the orange sky turns black and my friends head home. I notice I’m not feeling well, but chalk it up to smoking too much tobacco peppered in with weed, and try to lie down to sleep.

Five minutes later, I’m bursting out of the tent, furiously ripping open zippers and racing out on my hands and knees to eject my dinner all over the place. I’m trembling, tears in my eyes, but crawl back into my sleeping bag hoping the worst is over.

Five minutes later, I’m bursting out of the tent yet again, this time awkwardly powerwalking in the direction of the outhouse, but it might be too late…

Back in the tent, sufficiently traumatized, I’m drinking water and telling myself everything will be okay. But it’s just a brief interlude for, in another five minutes, I’ll be outside the tent again, expelling even water. In ten, I’ll be back in the latrine. And so the night repeats itself.

The next morning, I awaken under a mountain of blankets in a random yurt I commandeered in the middle of the night. Between puking and shitting myself, I was simply opposed to freezing my ass off also. I stumble out of the yurt and into the glaring sun – my craziest nights with a bottle of tequila never made me feel like this! I crash down into a plastic chair and lazily raise a bottle to take a few agonizing sips. The comforts of Skardu are within reach if I can muster the energy to get there, but the thought of simply packing my bike to leave seems interminable.

The roughest sections of road in the park are those east of Barapani, those I’m now riding. Sleep deprived, devoid of calories and bouncing over massive cobbles in the lowest gear, I feel like my consciousness is going to shake loose from my body. Everything feels like a dream, unreal, like a movie someone’s watching in a drug-intoxicated state. Sadly the drugs don’t cancel out the reality I’m facing up ahead, of a rugged hike-a-bike to Deosai Top.

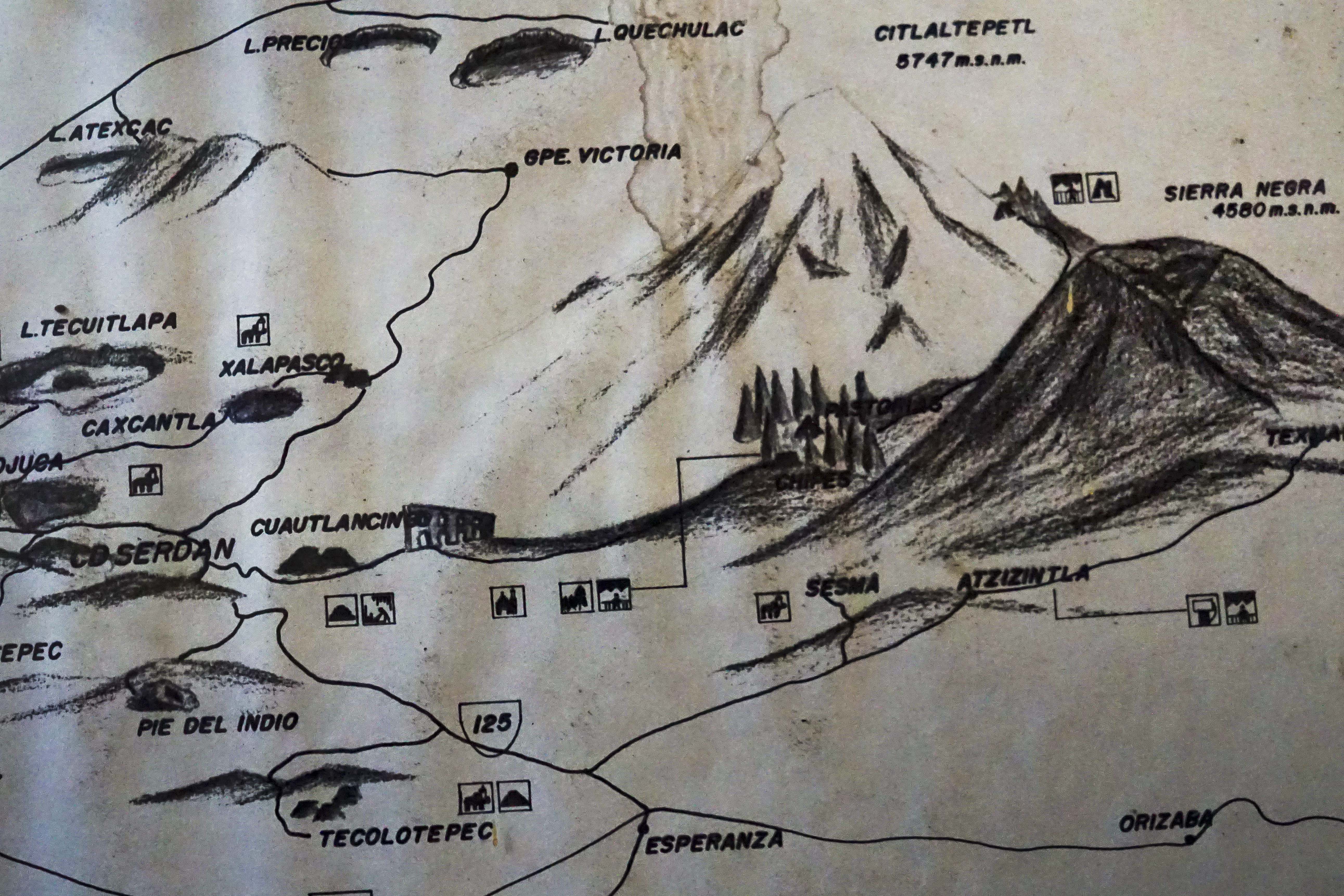

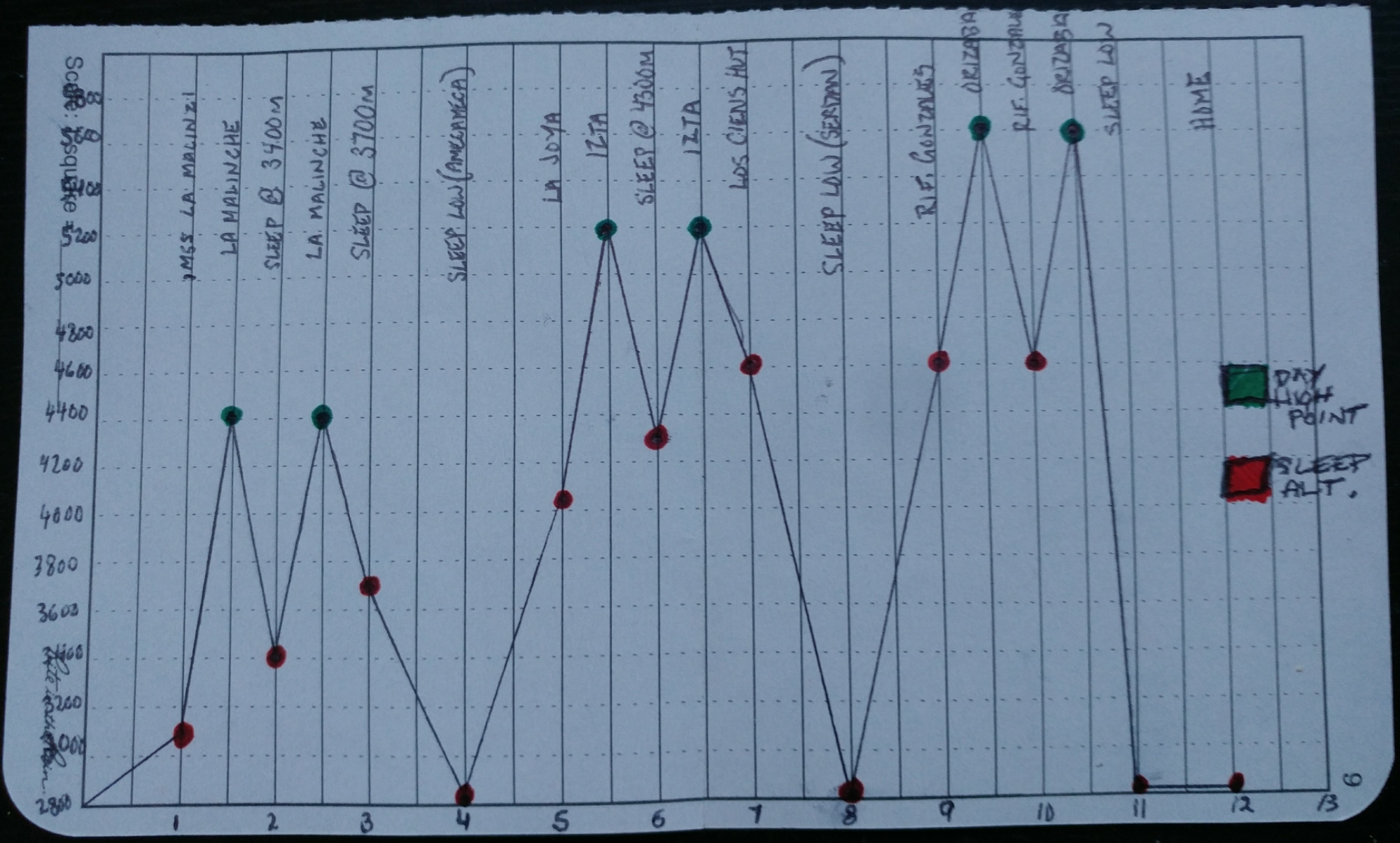

I won’t say it’s the worst hike-a-bike, for me, the push up to Orizaba wins that coveted spot. But upon arriving at Deosai Top and thinking the difficulties are over, expecting smooth sailing to Skardu, the sweet sense of victory is replaced by the frustration of even rougher roads.

The horrid jumble of rocks eventually gives way to pavement as I coast beside the slate-blue waters of Satpara Lake. This is a moment I envisioned a decade ago, at a time when I knew nothing about bike touring or endurance fitness. For some reason, I always pictured this part, but never expected I’d be in a funk because I was up all night puking my guts out and then getting rattled apart on the descent.

I sit down to roll a smoke, percolating with the feeling of irritation that comes with being too long on a bike, when along comes the buzz of a motorcycle. I’m a sitting duck, a foreigner with a bicycle no Pakistani can resist stopping to ask the usual fifty questions, and I’m in no mood for that.

“Keep going, keep going, keep going,” I plead, sitting still as a stone, as I listen to the noise get louder over one shoulder, then the other, as it seems to putter off into the distance. I’m relieved, thinking the threat gone, when I’m startled to hear the soft voice of a man calling to me from behind.

“Helloo?” he says, but I pretend I don’t hear.

“Helloo?” he repeats, and I turn around to find the sweetest little soul, standing there smiling toothlessly and positively brimming with the prospect of talking to a real, live foreigner. “What is your country?” he begins.

I get up and shake off my crabby countenance, and prepare to indulge the man’s fifty questions.

– SKARDU –

Skardu, 2,228 meters above sea level, is the sprawling gateway to K2 and the bigger mountains of the Karakoram Range. A dusty, roughhewn and normally bustling frontier town, I arrive to find the streets empty of vehicles or people on account of the Shia holiday of Ashura. Only a goat wanders, picking up what scraps he can find.

Shops are shuttered, as are hotels, and my only option is the dapper-looking Hotel Mashabrum. I’m shown to a lavish room with a balcony that overlooks the valley and hand over an exorbitant fare but don’t care. After last night in Deosai and the ensuing bumble to get here, I’m willing to pay for anything that resembles comfort.

A few hours later, I’m smoking a joint on the balcony and contemplating the ethereal atmosphere. The full moon shines over the valley and a breeze has kicked up the rustling of trees. One by one, the mosques intone their mantras, reverberating over the city like a choir of wailing, haunted voices. The hymn swells and cascades for an hour before each voice fades back into the moonlit night, leaving only the trees whispering their song.

The occasion is magical enough to warrant dragging out the prayer rug that comes standard in every hotel room and offering a few rakat. I raise my open hands and say, “God is great” and then bow down in respect.

Warm afternoon sun shines through drawn curtains as the ceiling fan slowly rotates. How many days have I been lying sick like this inside the Hotel Mashabrum? It started with a cramping in my stomach, but three days later I’m wire-thin and frail as I stagger into the bathroom to take yet another shit. Sidelined twice by illness, to say I’m demoralized is an understatement. I see no promise of continuing my trip.

There’s a knock on the door. I open it slightly to see the hotel manager looking very concerned. “Are you okay?” he asks. “We haven’t seen you in two days.” I reply that I’ve been sick, but agree to come downstairs and try to eat.

Improving somewhat, I decide to go for a walk. I pass the surly fruitsellers from whom I procure some grapes; the mechanic’s quarter, a veritable graveyard for Landcruisers; then wander down to the creek where linens are laundered and goats are grazed. I continue walking across the valley, past the last few houses, in search of the so-called Buddha Rock. Even Google fails to aid me as I flounder in the bushes looking for this monument from the ancient past.

In the forest, I stumble upon a small house. For a few rupees, a debilitated old man hobbles over and unlocks the gate. Inside, a giant gold flagstone is emblazoned with carvings of the skinny, cross-legged Buddha, supposedly dating from a time when this religion, not Islam, was the mainstay.

Buddha was emaciated and it was a good look, but I wonder how I’ll fare riding a hundred kilometers tomorrow in the same kind of state…

– HUSHE –

Alpenglow bathes the huge granite spires lined on the opposite side of the river from the traditional Balti village of Machulu. I push my bike out into the cool air and wave goodbye to my friends at the Felix guesthouse. I barely made it out the door this morning, between endless cups of tea and thoughts of our conversation that ran deep into last night. But here I am with no place left to go but Hushe.

It’s taken me two days to get here, a hundred kilometer push out of Skardu on the first day, followed by a tortuous, if brief, section of rough riding to get to Machulu. Now my bike is pointed at the gleaming white mountain at the head of the valley that is none other than Mashabrum.

Gradually the valley’s peaks come into view, each one an adventure in architectural conception, offending in scale, improbable in design. I ride my bike along a dusty track that is none other than a gallery of the finest mountains I have ever seen. Every curve in the road reveals new forms more astounding than those that came before. This is the reason I came to the Karakoram in the first place, to feast my eyes upon its monolithic granite sculptures.

I pedal along beside a rushing river that has cut into the surrounding moraine over centuries, my rear tire straggling in the silty white sand. Lacking the flotation of a full-blown fatbike, I’m forced to get off and walk.

A truck appears as I’m pushing my bike, the first I’ve seen all day. Tariq is a mountain guide from Hushe, returning home with a collection of whitebearded elders. I pass my hand around, saying salaams, before assuring Tariq no, despite appearances, there’s nothing wrong with my bike and I don’t need a ride to Hushe.

“Do you like to hike?” he asks, inquiring if I’d like to trek in the mountains around Hushe. Hiking is a different story, I tell him, and agree to meet him at the Refugio Hotel.

My arrival is like a scene from a movie. Approaching the outskirts, people are waving and welcoming me to Hushe. Soon, every young male in the village is following behind me like a giant parade, marching merrily along to the Refugio. I show up with my flock to find Tariq leaning against his truck.

“You must be hungry,” he says.

In the dining room, I voraciously shovel karahi into my mouth while Tariq sits in his puffy coat, quietly watching me. Tariq is a hardcore climber in his own right, having been to the summits of K2 and Broad Peak. Attempting both in the winter is a whole other matter. He scrolls through images on his phone, showing me famous climbers he’s been on a rope with. Old black and white photos of bygone expeditions adorn the walls of the dining hall. No jeep can take you to basecamp; Hushe is the last place you can drive before you have to tighten up your boots and start walking.

Tariq promises to show me the upper reaches of the valley the next day. We meet at dawn, his shambly Landcruiser rumbling up to the Refugio. Tariq shoulders a decades-old pack as we start walking, fiery sunrays alighting the pinnacles above Hushe.

Tariq leads me along broad gravel flats, up through goat herds lounging in luxurious alpine groves, then through dross moraine, underneath slabs of stone unseemly in scale. Through the wasteland my guide and I march, to a spot he has brought me to see the Mashabrum Glacier, black and gratuitously spewing its discharge.

Grey stormclouds have appeared and a cool wind suddenly picks up. “The weather is changing,” says Tariq stoically, looking around at the sky.

We stumble down through the boulders until Tariq suggests a pit-stop. He leads me over to where there are a few small huts for the use of shephards, bounded by walls of neatly stacked stones. An impeding goat stands between us and a few raps on the hatch, which is opened after much delay. The hut is residence to three aging occupants presently engaged in a fervent, if lighthearted, bickering among themselves.

We seat ourselves around the crackling fire. A huge jug of fresh milk is passed overhead and poured into a pot on the open flame. Conversation zips back and forth inside the darkened hut, none in any language I can understand. The tea is ladled with infinite finesse, forming a thick broth that comes to me in a scalding cup. The veterans shoot back the liquid almost immediately but I’m forced to nurse the cup in my lap for a bit, until tepid enough to touch my lips, soaking into my soul.

– LAHORE –

It’s with mixed feelings that I leave Hushe with my bike in the back of Tariq’s Landcruiser. He’s offered to drive me back to my starting point in Gilgit, allowing me to save three days of riding on some notoriously nasty roads. As we drive, however, I can’t help but imagine what it would be like to ride these parts and a bitter resentment comes over me. I remind myself that me riding in this steel box has a motive. While it breaks my heart to leave the Karakoram after so brief an affair, I’ve got a liaison with Lahore.

We return to the Park Hotel where my bike bag is found stuffed in a closet. My final soiree in Gilgit is a trip to the market to secure the implements needed for my excursion to Lahore. I visit around and take tea with the shopkeepers selling similar selections of beads and shawls. The night is concluded dining with an influential gem seller who, despite his efforts to attend to conversation, is distracted by the persistent ringing of his phone.

The bus ride to Lahore is so sedate that I’m totally unprepared for the intensity of my arrival. A wily rickshaw driver races through traffic and deposits me in front of the Best Western – long closed. So I start strolling and check in to the first place I see, Sultan’s Palace.

I have the suspicion I’m the first foreigner they’ve had at this hotel. In fact, I’m possibly the first white person they’ve ever seen. The sari-clad girl at the desk smacks her bubblegum with indifference while the bellboy just stares at me in wonder. They bring out the Sultan’s apprentice to aid the negotiation which just grows more tense.

I’m taken downstairs and introduced to the Sultan, looking like a barrister in his study. He informs me in perfect English that I’ll need to register with the authorities if I wish to stay at this hotel or any other in Lahore.

I jump on the back of the apprentice’s motorbike and we whiz through traffic, cigarettes in our mouths and a piece of hand luggage precariously dangling from my arm. We stalk the halls of one police station, poking our heads in offices, getting redirected to other offices, then being sent across town. We roam a second police station only to be sent to a third. This happens one more time before we finally track down the right authorities.

We walk into what feels like a brutally formal meeting of high-ranking officers. I do not need to register, a mushachioed colonel tells me.

“We have no objection to Canadians in Lahore,” he says. However, it is added that I will “need security”. To me, this implies a reluctant policeman attached to my hip, who would most certainly constrain my ability to roam the city as I please.

“This is a requirement?” I ask.

“No, no, no,” the colonel goes on. “It is simply a recommendation for your safety.”

After thanking them for their time, we leave. Me and my accomplice walk out into the glaring sunshine and put on our shades.

“Should we go to the security briefing?” he asks.

“Fuck that,” I say, and we get back on the bike and go to the hotel.

After one night at Sultan’s Palace, I need to find another jumping-off point to explore the Walled City. My search incidentally brings me to the fanciest hotel in Lahore.

Without a doubt, I am not sophisticated enough to be a guest at this hotel, which caters to suit-and-tie types, foreign diplomats, the upper echelons of society. I barely made it inside past the paramilitary security perimeter, now even the waiter is loath to look at me so I can order some breakfast.

In my room, I slip into the garments I procured in Gilgit for the purposes of looking the part of an unassuming northerner, so as to go out on the town undetected. A rose-colored kurta is paired with slender white trousers that draw to a close tightly around the ankle. A raggedy keffiyeh about the shoulders completes the look. All I need now is the right kind of walk – the Pakistani strut – to penetrate the Walled City without anyone blinking an eye.

As I walk through Delhi Gate, it feels like toppling through a portal backwards in time. Rows of shops are beginning to open, cloistered below fluttering canopies. The morning light barely reaches beyond the wanton web of electrical wiring strung between tottering havelis. I get lost in the maze of corridors grouped by area of specialty: the shoemaker’s bazaar; the bicycle bazaar; the ladies’ fashion bazaar, glowing like a neon acid trip. I get lost in back alleys where children run and and cats roam. Everything feels ancient, weathered by centuries, every surface like it has a story to tell.

My wanderings lead me to the ornately decorated Wazir Khan mosque, where I pitch a few rupees to the shoe-minder and step inside to pray namaz. My feet are caked in dirt from walking the streets of Lahore, underlining the prescription to give them a ritual wash before stepping inside to pray.

My last stop is Badshahi Mosque, majestic heirloom of the Mughal era which, when I stumble upon it late in the day, is like a temple of serenity and peace. I step through the gate into an elaborate courtyard encompassing a grand prayer hall hued the same pink as the sky and topped with three enormous white domes. The group prayer is about to begin so I hurry to take a spot in line with the other men*. After prayer, I retire to a quiet corner to turn my beads a few rotations in the manner of a meditative Sufi.

*Women pray in adjacent room.

I lounge awhile on the grounds of Badshahi, taking in its supreme sublimity, before weaving my way back through the alleys of the Old City after dark.

Returning to the hotel, I’m halted by frowning faces assailing me with a barrage of questions in Urdu. Forgetting I’m wearing Pakistani garb, I realize my gaunt and unshaven look likely has the appearance of some Afghan mujahideen who’s spent too many a day out in the field. A figure who doesn’t belong here and can’t be up to any good.

A few words in English are enough to disarm the situation, their hostile faces breaking into awkward laughter like they’re the victims of a practical joke. I saunter past the grand piano and into the elevator, which rises high above jewelled chandeliers. I laugh at the contradiction: the epitome of luxury in a city of squalor and here I am, a poor Pashtun, something to be shooed away like a stray animal.

– ISLAMABAD –

After two weeks off hash, I’m uncomfortably high. Feroz has just returned from Peshawar with a ball of sticky black charas he’s eager to try, so we retreat to the gaudy green hotel to dig in.

Staring at Feroz, my vision tunneling deeper, a halo radiates from around his demonic head. I’m convinced he’s going to kill me, the way he coldly sits there, sizing me up, premeditating my murder. This is it, he was waiting till now to satisfy his bloodlust! But that isn’t the kind of lust Feroz is feeling. He’s fixated on getting us a hooker.

Sitting in the dim haze, smoke streaming from the end of the joint, he leans forward and confides: “I like beef, you know?”, then gestures to indicate a heavy woman with large breasts and thighs. “Not single,” he says, meaning a skinny woman. “Not good for fuck.”

Feroz’ family life is no impediment to visiting his “girlfriends” whose husbands work in Dubai. He’s arranged to shop these girls out in the meantime, generating a little extra cash for everyone in the process.

He asks what type of girl I like, and I say it doesn’t matter to me if a woman is big or little, what’s important is that she’s pretty. I point to the actresses on the soap opera we’re watching. For such a conservative country, many women on Pakistani TV wear their hair uncovered and are drop-dead gorgeous.

This idea has never occurred to Feroz, so it seems to disqualify the “girlfriends” he had in mind. Then he has idea. There’s a red-light district where one can find any kind of courtesan one desires, picking them off a page like an entree at a restaurant.

“In the marketing area,” he says, “anything is available. Any girl, any beauty.”

His last ditch is to suggest we round up a couple girls and go to Murree, a hill station outside of Islamabad. He’s been singing the praises of Murree ever since I got here, so for one last day, we’ll compromise.

“Okay,” I say. “No girls. Just you and me. Let’s drive up to Murree for the day and come back to Islamabad tomorrow night.”

If Feroz is anything, he’s resourceful, and in every corner knows a trusty hotel owner in whose establishment he can safely get high. Murree is no different, as we slowly savor fumes with with his old friend. Murree is a popular spot to flock, evidenced by what sounds like a dance party next door. Otherwise, our friend’s silk shirt, slicked-back hair and enormous gold ring suggest that business isn’t bad.

Feroz and I take the rickety chairlift up to the top of Pindi Point to admire the view, but it’s already becoming obscured by clouds. Tendrils of fog stream over the hillside on which Murree sits, creeping down avenues and blotting out the town. Feroz is filled with amazement as we watch. As someone mostly confined to a hot and smoggy city, he’d been trying to explain the novelty of this place, where the cooling mists intermingle with the hills.

He jabs me in the shoulder and points at the rolling fog. “You see? The weather, it comes down!”

Clouds are forerunner to rain, so we order do chai and wait out the storm under a fluttering tarp. Once the rain lets up, we make a break for the chairlift, but get loaded on just as the rain resumes and are stuck, held captive in the mortifying sprinkle. The tattered, rainbow-colored umbrella mounted above does nothing to prevent us from getting completely soaked.

When we get to the bottom and are released from the tortuous chairlift ride, Feroz asks if I’ll take a picture. “What?” I say, about to beeline it to the car. But he wants a picture of himself with the chairlift station and asks if I’ll take one. So I oblige, capturing the image of a man who is king of vice, dealer of temptation, my Pakistani Mephistopheles, standing and smiling contentedly in front of one of life’s simple pleasures.

This story has no climax. If there is one, it was two weeks back, riding across Deosai or into Hushe. It ends like it begins, on the white tiles in the open-air terminal at Islamabad airport. Feroz sucks back and jettisons a glowing butt that gets swept up by the broom of a passing janitor.

I could say some trite bullshit about how much I loved this place, how challenging my trip was, or the lessons I learned. But I just scraped the surface, I’m cognizant of that, and while standing here waiting for my departure, I’m hungry to come back for more.

“Thanks,” I say to Feroz, and he looks at me confused.

“For what, ‘thanks’?” he says.

“Thanks… for everything, I guess.”

“You are brother,” he says. “This is no ‘thanks’.”

Feroz is a man of metaphysical extremes: I am always afforded the height of chivalry and respect, yet in the same breath he’s always trying veer me into some fairly nefarious things. He was a contradiction, like the country itself, a whole mosaic of them, interwoven like the pattern of a Persian rug.

It’s what I was going to miss the most. But as I bid Feroz a hearty salaam and wheel my bike bag towards the departure gate, I have the funny feeling this isn’t the last I’ll be seeing of him or his country.

– Bikepacking Trip Summary –

05/09/19 Gilgit to Jaglot – 52km/385m

06/09/19 Jaglot to Astor – 56km (picked up after 25km/495m)

07/09/19 Astor to Chillam – 54km

08/09/19 Chillum to Barapani – 36km/~800-1000m

09/09/19 Barapani to Skardu – 50km/403m

10-12/09/19 Skardu (rest/sick)

13/09/19 Skardu to Khaplu – 98km/878m

14/09/19 Khaplu to Machulu – 15km/~100m? but brutal road, had to push a lot

15/09/19 Machulu to Hushe – ~30km/~500m

▲

I’m being escorted out of the airport by security who say “no bikes”, even though I just spent over an hour putting mine together outside Starbucks between sips of latte. Now, however, it’s “no bikes” but that’s convenient because it’s time for me to leave the airport and face the whirlwind that is Mexico City.

I’m being escorted out of the airport by security who say “no bikes”, even though I just spent over an hour putting mine together outside Starbucks between sips of latte. Now, however, it’s “no bikes” but that’s convenient because it’s time for me to leave the airport and face the whirlwind that is Mexico City. I must be getting close, because there are so many people that I have to get off my bike and walk. It’s Sunday: vendors are out, indigenous Nahuatl dancers are putting on a show, and people of all walks throng about, eating street food and taking pictures of everything.

I must be getting close, because there are so many people that I have to get off my bike and walk. It’s Sunday: vendors are out, indigenous Nahuatl dancers are putting on a show, and people of all walks throng about, eating street food and taking pictures of everything.

Heads up, eyes peeled. Fugazi is blasting in my headphones as I mash at the pedals, darting in and out of lanes and drafting in the wake of colectivos. Traffic isn’t heavy, but it’s fast, and it’s exhilarating to ride around the way most Mexico City drivers do — by not giving a fuck.

Heads up, eyes peeled. Fugazi is blasting in my headphones as I mash at the pedals, darting in and out of lanes and drafting in the wake of colectivos. Traffic isn’t heavy, but it’s fast, and it’s exhilarating to ride around the way most Mexico City drivers do — by not giving a fuck. Arriving in Amecameca, I embrace a lukewarm shower and a huge sandwich at the torta shop. Altzomoni Hut is closed, according to the woman at the national park headquarters, but it only puts a minor kink in my plans to climb Iztaccihuatl. The black stormcloud hanging overtop of Izta threatens to pose another.

Arriving in Amecameca, I embrace a lukewarm shower and a huge sandwich at the torta shop. Altzomoni Hut is closed, according to the woman at the national park headquarters, but it only puts a minor kink in my plans to climb Iztaccihuatl. The black stormcloud hanging overtop of Izta threatens to pose another.

The road is paved and meanders in wide switchbacks, granting increasingly wider views of the valley below. The foreground scenery is also noticeably green and verdant. The going is tough but not impossible, and my performance is enhanced by a warm Fanta from one of the spartan snack shacks along the way.

The road is paved and meanders in wide switchbacks, granting increasingly wider views of the valley below. The foreground scenery is also noticeably green and verdant. The going is tough but not impossible, and my performance is enhanced by a warm Fanta from one of the spartan snack shacks along the way. One hour later, the elements show no sign of stopping. I’m bundled in all my layers. I already drank one Nescafe, but I’m starting to shiver, and thinking about brewing up another. But in my periphery, I see movement.

One hour later, the elements show no sign of stopping. I’m bundled in all my layers. I already drank one Nescafe, but I’m starting to shiver, and thinking about brewing up another. But in my periphery, I see movement. It’s almost dark, and the red light is flashing furiously on the back of my bike. The pass has got to be close. I leapfrogged in front of Davy Crockett and he’s following somewhere behind me. My mind is reeling: If he likes to skin animals, maybe he wants to skin a gringo… So I’m pushing my bike real fast up this hill now.

It’s almost dark, and the red light is flashing furiously on the back of my bike. The pass has got to be close. I leapfrogged in front of Davy Crockett and he’s following somewhere behind me. My mind is reeling: If he likes to skin animals, maybe he wants to skin a gringo… So I’m pushing my bike real fast up this hill now. A little doggie accompanys me. It’s cold, and I’m rushing to set up the tent and boil a package of ramen noodles — habanero flavor I discover, upon taking the first sip. I need to recover at least 1000 calories, and they all sear on the way down.

A little doggie accompanys me. It’s cold, and I’m rushing to set up the tent and boil a package of ramen noodles — habanero flavor I discover, upon taking the first sip. I need to recover at least 1000 calories, and they all sear on the way down. I’m gripping the brakes, descending down a washboard dirt road for at least the last hour. My bags are threatened of being shaken off my bike, and I readjust my helmet which has sunken over my eyes, in an effort to squint through the fog.

I’m gripping the brakes, descending down a washboard dirt road for at least the last hour. My bags are threatened of being shaken off my bike, and I readjust my helmet which has sunken over my eyes, in an effort to squint through the fog. I should be in Cholula in no time, I say, expecting a thousand-meter descent on smooth pavement to deliver me to a steaming plate of eggs and coffee. But here I am, white-knuckled and weaving between massive rocks on a road that is, “at least sometimes passable by 4-wheel-drive vehicles,” as per the most cursory of sources on the Internet. Trip research fail.

I should be in Cholula in no time, I say, expecting a thousand-meter descent on smooth pavement to deliver me to a steaming plate of eggs and coffee. But here I am, white-knuckled and weaving between massive rocks on a road that is, “at least sometimes passable by 4-wheel-drive vehicles,” as per the most cursory of sources on the Internet. Trip research fail. Finally, a mountain. Just a mountain. I’m not fighting my way out of a city, or pushing my bike up endless switchbacks, or lost on some God-forsaken backroad. I’m simply walking up a mountain, an easy one, and one I’ve walked up before: La Malinche.

Finally, a mountain. Just a mountain. I’m not fighting my way out of a city, or pushing my bike up endless switchbacks, or lost on some God-forsaken backroad. I’m simply walking up a mountain, an easy one, and one I’ve walked up before: La Malinche. I crest the ridge as tendrils of cloud are uplifted by the mountain, standing alone in the landscape for a hundred kilometers in every direction. Arriving at the summit, I face a veritable party dominated by… Germans? But the views from this “easy” mountain have me transfixed. You actually can’t see much because of the clouds, but through brief glimpses of crumbling rock in the caldera, I’m given a vision of heaven and hell.

I crest the ridge as tendrils of cloud are uplifted by the mountain, standing alone in the landscape for a hundred kilometers in every direction. Arriving at the summit, I face a veritable party dominated by… Germans? But the views from this “easy” mountain have me transfixed. You actually can’t see much because of the clouds, but through brief glimpses of crumbling rock in the caldera, I’m given a vision of heaven and hell.

With ninety degrees’ change of direction comes a 180° reversal of luck. I’ve hit a headwind that batters every effort to make forward progress, and still have 40 kilometers to go. The road’s definitely no longer downhill. It looks flat, but it feels like I’m riding up a mountain.

With ninety degrees’ change of direction comes a 180° reversal of luck. I’ve hit a headwind that batters every effort to make forward progress, and still have 40 kilometers to go. The road’s definitely no longer downhill. It looks flat, but it feels like I’m riding up a mountain. After a long, bonky crusade against the wind and exhaustion, I arrive at the Hotel Montecarlo, a true refuge for the mountaineer in this part of Mexico, compared to the crude shipping crates which pass for huts up high. It feels surreal to be here again but with my bike as means of transport.

After a long, bonky crusade against the wind and exhaustion, I arrive at the Hotel Montecarlo, a true refuge for the mountaineer in this part of Mexico, compared to the crude shipping crates which pass for huts up high. It feels surreal to be here again but with my bike as means of transport.

I poke around the last village in hope of a taco shop or something to satiate my desire for lunch, and realize there’s little more here than a bunch of houses. The sound of artillery fire is atrocious, and my entire body is punctuated by a shockwave when one unexpectedly goes off.

I poke around the last village in hope of a taco shop or something to satiate my desire for lunch, and realize there’s little more here than a bunch of houses. The sound of artillery fire is atrocious, and my entire body is punctuated by a shockwave when one unexpectedly goes off. “Pico de Orizaba?” I ask, pointing in the general direction of the mountain.

“Pico de Orizaba?” I ask, pointing in the general direction of the mountain. “You said you wanted to suffer!” I yell, in between expletives and gasping for oxygen. I can’t deny that I did. And while this is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done, I’m conscious that this is exactly what I asked for.

“You said you wanted to suffer!” I yell, in between expletives and gasping for oxygen. I can’t deny that I did. And while this is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done, I’m conscious that this is exactly what I asked for. Altitude I’m cool with. Endurance, sure. But this is like some kind of Herculean punishment, like pushing a rock up a mountain that continually rolls back down.

Altitude I’m cool with. Endurance, sure. But this is like some kind of Herculean punishment, like pushing a rock up a mountain that continually rolls back down.

A half-hour later, I’m out the door. “Maybe I’ll get a headstart on the rest of the climbers,” I say, but can already see a line of twinkling dots scaling what I assume is the Ruta Sur.

A half-hour later, I’m out the door. “Maybe I’ll get a headstart on the rest of the climbers,” I say, but can already see a line of twinkling dots scaling what I assume is the Ruta Sur. I reach the wall of steep, loose scree that is mainly a nuisance, but a risk to one’s life in the most inane way: rocks are easily dislodged here and this final stretch is not only slow due to altitude and terrain, but also a shooting gallery of debris kicked down by parties up above.

I reach the wall of steep, loose scree that is mainly a nuisance, but a risk to one’s life in the most inane way: rocks are easily dislodged here and this final stretch is not only slow due to altitude and terrain, but also a shooting gallery of debris kicked down by parties up above. Back at the dungeon, six hours later, I’m being interrogated by two boys who want to know everything about my bike, where I came from, and where I’m going next.

Back at the dungeon, six hours later, I’m being interrogated by two boys who want to know everything about my bike, where I came from, and where I’m going next. After climbing Orizaba, I’ve earned the easy part: a three kilometer descent on my bike. Putting that in perspective, it’s a big drop. Like cycling down two Banff mountains stacked on top of each other, no pedaling required.

After climbing Orizaba, I’ve earned the easy part: a three kilometer descent on my bike. Putting that in perspective, it’s a big drop. Like cycling down two Banff mountains stacked on top of each other, no pedaling required.

But there’s a hotel here in Soledad de Doblado, I’m told, and I’m racing through the streets behind an ATV that’s offered to take me there. I go up the steps of Hotel Jardin and an old lady looks at me contemptfully. With a wrinkled nose she takes my 200 pesos and shows me to a dilapidated room. The bed is sunken in the middle and insects scurry when I pull back the sheets. Faded Toy Story curtains round out the decor.

But there’s a hotel here in Soledad de Doblado, I’m told, and I’m racing through the streets behind an ATV that’s offered to take me there. I go up the steps of Hotel Jardin and an old lady looks at me contemptfully. With a wrinkled nose she takes my 200 pesos and shows me to a dilapidated room. The bed is sunken in the middle and insects scurry when I pull back the sheets. Faded Toy Story curtains round out the decor.

Legs madly spinning into a wall of resistance, I’m growling through clenched teeth. I desperately look at the altitude on my watch, expecting to see it drop towards zero, but the number is going up, not down. Today’s supposed to be a descent to sea level — why am I still climbing then?

Legs madly spinning into a wall of resistance, I’m growling through clenched teeth. I desperately look at the altitude on my watch, expecting to see it drop towards zero, but the number is going up, not down. Today’s supposed to be a descent to sea level — why am I still climbing then? I come around the corner of a pastel-colored hotel and see the blue expanse. I’m not sure if there is relief, or just shellshock. I cross the street and there’s a sense of, “Wow, I did it, I’m really here”, as I ride along the waterfront but, honestly, I just feel numb.

I come around the corner of a pastel-colored hotel and see the blue expanse. I’m not sure if there is relief, or just shellshock. I cross the street and there’s a sense of, “Wow, I did it, I’m really here”, as I ride along the waterfront but, honestly, I just feel numb.

As I sit beside my giant box repeating the F-word, my guardian angel appears on a white moped. I assault him with questions, assuming he works in cargo. He is very kind with my desperation. He’s actually a ticket agent and suggests we go back to the airport. He wants to know exactly what happened and leaves to speak with his colleagues. After a couple minutes, he comes back and says, “Mr. Amaral, we can transport your box.”

As I sit beside my giant box repeating the F-word, my guardian angel appears on a white moped. I assault him with questions, assuming he works in cargo. He is very kind with my desperation. He’s actually a ticket agent and suggests we go back to the airport. He wants to know exactly what happened and leaves to speak with his colleagues. After a couple minutes, he comes back and says, “Mr. Amaral, we can transport your box.”

I didn’t want it to go on

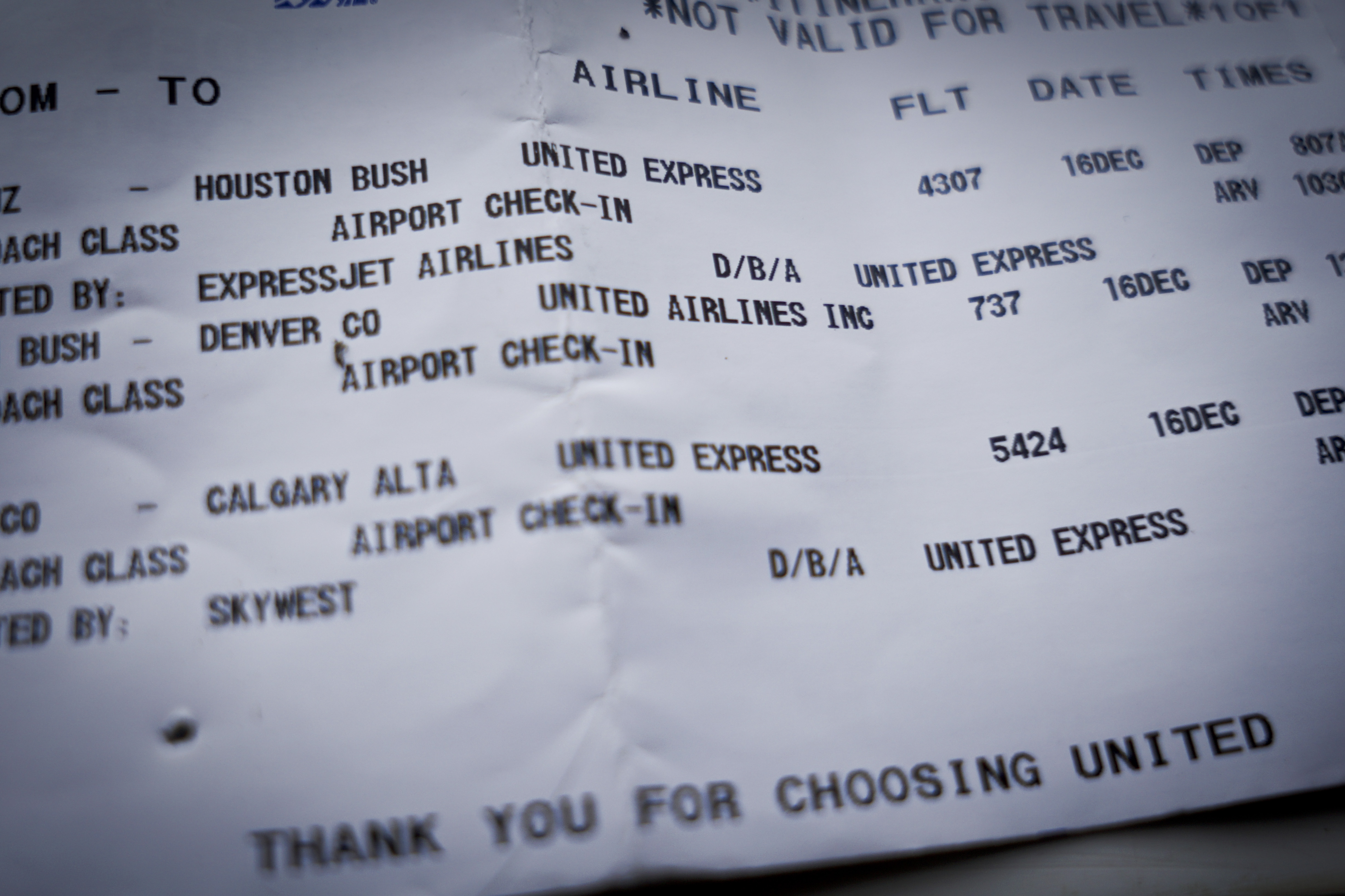

I didn’t want it to go on  At first, I couldn’t even admit to myself what I was doing. Meanwhile, another part of my mind, somehow divorced from conscious acceptance, dutifully did tasks to get ready for the trip − re-learning Spanish, working on my bike, gathering stuff for the trip, etc. Yet I still couldn’t admit to myself what I was intending to do.

At first, I couldn’t even admit to myself what I was doing. Meanwhile, another part of my mind, somehow divorced from conscious acceptance, dutifully did tasks to get ready for the trip − re-learning Spanish, working on my bike, gathering stuff for the trip, etc. Yet I still couldn’t admit to myself what I was intending to do. Two weeks left, and the black crow still circled. I had to call my parents. I had to tell them what I was doing, and I knew they’d think it was a bad idea. I already felt a bit disconnected from my family, maybe even seen as aloof. I couldn’t let my parents learn I was riding my bike across Mexico by tuning into Instagram, or from my brother mentioning it offhandedly. This was my vocation, not just a hobby, and I had to call my parents and explain what I intended to do.

Two weeks left, and the black crow still circled. I had to call my parents. I had to tell them what I was doing, and I knew they’d think it was a bad idea. I already felt a bit disconnected from my family, maybe even seen as aloof. I couldn’t let my parents learn I was riding my bike across Mexico by tuning into Instagram, or from my brother mentioning it offhandedly. This was my vocation, not just a hobby, and I had to call my parents and explain what I intended to do. One week to go. All the pieces were seemingly in place except I hadn’t truly committed. I thought I’d severed and peeled apart the layers of my discomfort about this trip − by admitting to myself, telling others, telling peers, and telling my family − yet a kernel of reluctance remained. Did I even want to do this? Did I have the mental or physical capability?

One week to go. All the pieces were seemingly in place except I hadn’t truly committed. I thought I’d severed and peeled apart the layers of my discomfort about this trip − by admitting to myself, telling others, telling peers, and telling my family − yet a kernel of reluctance remained. Did I even want to do this? Did I have the mental or physical capability? It didn’t matter whether I wanted to do this. It didn’t matter if I was strong enough. And it didn’t matter if I was scared. I was being an enormous pussy, and it sickened me.

It didn’t matter whether I wanted to do this. It didn’t matter if I was strong enough. And it didn’t matter if I was scared. I was being an enormous pussy, and it sickened me.

Five o’clock. The sun hasn’t dawned on the tip of Cascade yet. On goes the espresso maker with a flick of the switch. It’s another morning meeting Chris for a pre-dawn skin up Sunshine or John for a session of climbing ice.

Five o’clock. The sun hasn’t dawned on the tip of Cascade yet. On goes the espresso maker with a flick of the switch. It’s another morning meeting Chris for a pre-dawn skin up Sunshine or John for a session of climbing ice. At work, I nag John to see if he wants to go ice climbing. Our relationship is mutually beneficial; I can learn a lot from climbing with John, and he needs a partner to go with, so he agrees. A little something in the backyard of Canmore is arranged for working on skills, not so much a backcountry outing.

At work, I nag John to see if he wants to go ice climbing. Our relationship is mutually beneficial; I can learn a lot from climbing with John, and he needs a partner to go with, so he agrees. A little something in the backyard of Canmore is arranged for working on skills, not so much a backcountry outing. Copious breakfast is consumed and workplace politics dissected. We rock up to the Junkyards, “thriftstore alpinists” John calls us. We do a couple laps on Scottish Gully then trade ropes with another party and try their steeper pitch. Lunch is conducted as Kananaskis Public Safety bomb the flanks of East End of Rundle, a very “Apocalypse Now”-ian scene as John surveys the damage while I implore my Bialetti to hurry up and boil.

Copious breakfast is consumed and workplace politics dissected. We rock up to the Junkyards, “thriftstore alpinists” John calls us. We do a couple laps on Scottish Gully then trade ropes with another party and try their steeper pitch. Lunch is conducted as Kananaskis Public Safety bomb the flanks of East End of Rundle, a very “Apocalypse Now”-ian scene as John surveys the damage while I implore my Bialetti to hurry up and boil. The day is concluded with a rap down Scottish Gully to bring down our rope, followed with practice lead climbing a moderate pitch. We get back to the car in the dark, John having an eight hour night shift ahead of him that evening.

The day is concluded with a rap down Scottish Gully to bring down our rope, followed with practice lead climbing a moderate pitch. We get back to the car in the dark, John having an eight hour night shift ahead of him that evening. A stunner day riding the lift to the top of North American at Norquay. It feels like the first taste of spring. I have a pass but yesterday I skinned (read: bootpacked) up here from town for shits and giggles. Today I’m just riding bumps. And steep cruddy crap, even though a few days ago this place was pow-city. Oh well, at least the sun feels nice on my face.

A stunner day riding the lift to the top of North American at Norquay. It feels like the first taste of spring. I have a pass but yesterday I skinned (read: bootpacked) up here from town for shits and giggles. Today I’m just riding bumps. And steep cruddy crap, even though a few days ago this place was pow-city. Oh well, at least the sun feels nice on my face. It’s the end of the month and Chris and I are ready for something beyond the whole Sunshine thing. I’m used to riding steep terrain in shitty conditions; the skiing might not be pretty but I can make it down the hill. So obviously I’m ready to ski a couloir in the backcountry. Chester Lake is suggested and although I expect/hope for Chris to talk me out of it, he seems enthusiastic. Fuck.

It’s the end of the month and Chris and I are ready for something beyond the whole Sunshine thing. I’m used to riding steep terrain in shitty conditions; the skiing might not be pretty but I can make it down the hill. So obviously I’m ready to ski a couloir in the backcountry. Chester Lake is suggested and although I expect/hope for Chris to talk me out of it, he seems enthusiastic. Fuck. After a few kilometres of easy skinning, we rock up to the huge fan at the base of the couloir and put our skis on our packs. Out come the ice tools and crampons for eight hundred metres of frontpointing. We make good progress up the slope, alternately taking turns to break trail and kick steps for each other, though it’s hard work.

After a few kilometres of easy skinning, we rock up to the huge fan at the base of the couloir and put our skis on our packs. Out come the ice tools and crampons for eight hundred metres of frontpointing. We make good progress up the slope, alternately taking turns to break trail and kick steps for each other, though it’s hard work. A short distance below the top, the climbing turns to wallowing in unconsolidated powder so we say “fuck it” and put on our skis. Chris goes first, his first few turns unsuccessful. He navigates down a narrow section, then I go. The same. I might be used to riding steep terrain, but not in powder, and most of my turns leave me resignedly lying like a heap in the snow. I laugh, but it’s frustrating.

A short distance below the top, the climbing turns to wallowing in unconsolidated powder so we say “fuck it” and put on our skis. Chris goes first, his first few turns unsuccessful. He navigates down a narrow section, then I go. The same. I might be used to riding steep terrain, but not in powder, and most of my turns leave me resignedly lying like a heap in the snow. I laugh, but it’s frustrating. Eventually we make a few good turns down the gully. Chris skis down the fan and out of sight. Suddenly the powder turns into ice and my skis are skating down the slope. I’m in an uncontrolled glissade and headed directly for some rocks and/or a cliff. I strike with my ice tool and it’s wrenched out of my hand. I desperately plunge my ski pole into the ice and drive it in with more and more pressure until I slowly and painstakingly come to a stop. My skis dangle from my toe pins, ice tool still planted in the slope fifty metres above me. Otherwise I’m unscathed, save for my dignity. Yeah, so ready to ski a couloir…

Eventually we make a few good turns down the gully. Chris skis down the fan and out of sight. Suddenly the powder turns into ice and my skis are skating down the slope. I’m in an uncontrolled glissade and headed directly for some rocks and/or a cliff. I strike with my ice tool and it’s wrenched out of my hand. I desperately plunge my ski pole into the ice and drive it in with more and more pressure until I slowly and painstakingly come to a stop. My skis dangle from my toe pins, ice tool still planted in the slope fifty metres above me. Otherwise I’m unscathed, save for my dignity. Yeah, so ready to ski a couloir… The Bialetti sputtered on the stove and I raced over to rescue its contents. A map of Peru’s Cordillera Huayhuash hung on the wall, in a mundane spot beside the fridge so I would look at it every day, committing its lofty passes and peaks to memory.

The Bialetti sputtered on the stove and I raced over to rescue its contents. A map of Peru’s Cordillera Huayhuash hung on the wall, in a mundane spot beside the fridge so I would look at it every day, committing its lofty passes and peaks to memory. My dream of two years had been poached. I wasted no time bemoaning the situation or even considering trying to do it faster or unsupported; the whole point was to do a “first ascent” and that possibility was gone.

My dream of two years had been poached. I wasted no time bemoaning the situation or even considering trying to do it faster or unsupported; the whole point was to do a “first ascent” and that possibility was gone.

The self-powered style reached its zenith for me in the context of the Mount Temple Duathlon, in which I cycled 70kms from Banff to Moraine Lake, tagged 3544m Mount Temple, then rode all the way back to Banff. I completed this challenge twice this summer, the second time

The self-powered style reached its zenith for me in the context of the Mount Temple Duathlon, in which I cycled 70kms from Banff to Moraine Lake, tagged 3544m Mount Temple, then rode all the way back to Banff. I completed this challenge twice this summer, the second time  I can’t do a recap of this summer without mentioning my crack at the Temple FKT, which represents to me my sharpest, most refined state as a mountain runner. While the story is told

I can’t do a recap of this summer without mentioning my crack at the Temple FKT, which represents to me my sharpest, most refined state as a mountain runner. While the story is told  I’ll conclude with the last few episodes which come to mind:

I’ll conclude with the last few episodes which come to mind: Elizabeth Parker and Abbot Pass Huts with Marcy Montgomery. A little different for me as I’ve somehow spent six years in the Rockies avoiding carrying a heavy pack and/or doing overnight trips, but in terms of sheer enjoyment, this was one of my favourite weekends in the mountains, ever. Lake O’Hara was at its peak of golden larch season so the eye-candy was incredible and as for the company, the girl is a fucking riot.

Elizabeth Parker and Abbot Pass Huts with Marcy Montgomery. A little different for me as I’ve somehow spent six years in the Rockies avoiding carrying a heavy pack and/or doing overnight trips, but in terms of sheer enjoyment, this was one of my favourite weekends in the mountains, ever. Lake O’Hara was at its peak of golden larch season so the eye-candy was incredible and as for the company, the girl is a fucking riot.

It was mid-September. The mornings were chilly; leaves were turning vibrant yellow; snow had already fallen on the mountaintops. And there I was in my wetsuit about to slip into the freezing-cold lake.

It was mid-September. The mornings were chilly; leaves were turning vibrant yellow; snow had already fallen on the mountaintops. And there I was in my wetsuit about to slip into the freezing-cold lake. I actually possess a fair bit of experience both as a swimmer and dealing with mild hypothermia. I’ve been a swimmer my entire life, eventually teaching swimming as a young adult, where I shivered for hours in chilly lap pools with zero body fat to keep me warm.

I actually possess a fair bit of experience both as a swimmer and dealing with mild hypothermia. I’ve been a swimmer my entire life, eventually teaching swimming as a young adult, where I shivered for hours in chilly lap pools with zero body fat to keep me warm. When we awoke, the wind had died but the skies were dismal — you couldn’t even see Aylmer from the window as it was engulfed in dark clouds. We cooked a couple of breakfast wraps and headed out the door around 7:40am. I was already wearing my wetsuit so I wouldn’t have to change when we got to the lake.

When we awoke, the wind had died but the skies were dismal — you couldn’t even see Aylmer from the window as it was engulfed in dark clouds. We cooked a couple of breakfast wraps and headed out the door around 7:40am. I was already wearing my wetsuit so I wouldn’t have to change when we got to the lake. As I intended for this trip to be self-supported (i.e. carrying all my own gear), I planned to tow everything behind me in drybags bundled in a PFD. As we approached the water we could see a considerable chop flowing west into the Stewart Canyon outlet. “I’m not very optimistic about this,” I said considering I had yet to test the dynamics of my tow kit.

As I intended for this trip to be self-supported (i.e. carrying all my own gear), I planned to tow everything behind me in drybags bundled in a PFD. As we approached the water we could see a considerable chop flowing west into the Stewart Canyon outlet. “I’m not very optimistic about this,” I said considering I had yet to test the dynamics of my tow kit. I stumbled onto the opposite shore amid the beached driftwood grunting like a beast. Even though I was unbelievably cold, I had to change into dry clothes and start hiking immediately. Although the transition was slowed by the numbness of my extremities, once I got into my running gear and started moving, I warmed up quickly.

I stumbled onto the opposite shore amid the beached driftwood grunting like a beast. Even though I was unbelievably cold, I had to change into dry clothes and start hiking immediately. Although the transition was slowed by the numbness of my extremities, once I got into my running gear and started moving, I warmed up quickly. I traversed along the shoreline, stashed my wetsuit, then bushwacked up through the foliage to find Chris and Jordan.

I traversed along the shoreline, stashed my wetsuit, then bushwacked up through the foliage to find Chris and Jordan. The trail backtracks a bit before breaking out of the trees and gaining the location of the old lookout, which is no longer present. We gazed in the direction of Aylmer. Chris asked if a pointy peak, pretty far away, was Aylmer. No, I don’t think so, I said. We shifted our view a little. Even further away, behind that summit, was Aylmer.

The trail backtracks a bit before breaking out of the trees and gaining the location of the old lookout, which is no longer present. We gazed in the direction of Aylmer. Chris asked if a pointy peak, pretty far away, was Aylmer. No, I don’t think so, I said. We shifted our view a little. Even further away, behind that summit, was Aylmer. From the fire lookout, one traverses along the ridge towards its intersection with the avi gulch. This, I thought, would be straightforward, and though it wasn’t difficult, it was more bushwacky and route-findy than expected.

From the fire lookout, one traverses along the ridge towards its intersection with the avi gulch. This, I thought, would be straightforward, and though it wasn’t difficult, it was more bushwacky and route-findy than expected. Soon we arrived at the avi gulch to behold the behemoth Mt. Aylmer socked in the clouds. After a snack, we made our assault on the final mass of the mountain, aiming to dash up to the summit and back down to that spot.

Soon we arrived at the avi gulch to behold the behemoth Mt. Aylmer socked in the clouds. After a snack, we made our assault on the final mass of the mountain, aiming to dash up to the summit and back down to that spot. We traversed beneath the ridgeline and gained the notch in the ridge which permits views into the Ghost Wilderness on the other side. The final climb through loose rubble is nothing less than a slog, and compounded by relatively thin oxygen. If one consistently bags peaks in the 2500-3000m range (which in the Rockies is easy to do), one can expect to be feeling it at 3100m+.

We traversed beneath the ridgeline and gained the notch in the ridge which permits views into the Ghost Wilderness on the other side. The final climb through loose rubble is nothing less than a slog, and compounded by relatively thin oxygen. If one consistently bags peaks in the 2500-3000m range (which in the Rockies is easy to do), one can expect to be feeling it at 3100m+. As we ascended the final hundred meters, clouds rolled in and it started to snow. When I got to the top, I found Chris sitting on the summit grinning with nothing to be seen anywhere around him. I personally tagged the summit at 6h28m after leaving Banff — Chris was a few minutes before me and Jordan a couple minutes after.

As we ascended the final hundred meters, clouds rolled in and it started to snow. When I got to the top, I found Chris sitting on the summit grinning with nothing to be seen anywhere around him. I personally tagged the summit at 6h28m after leaving Banff — Chris was a few minutes before me and Jordan a couple minutes after. We hung around on the summit for only a few minutes, as there was nothing to see. I fixed the piece of lumber usually jammed in the summit cairn. We said, “Peace out, Aylmer,” and headed back down.

We hung around on the summit for only a few minutes, as there was nothing to see. I fixed the piece of lumber usually jammed in the summit cairn. We said, “Peace out, Aylmer,” and headed back down. The descent went smoothly. We boot-skiied through shitty rock to the notch, traversed along chossy ledges below the ridge, then bombed down the screefield in the avalanche gulch to meet up with the Aylmer Pass trail.

The descent went smoothly. We boot-skiied through shitty rock to the notch, traversed along chossy ledges below the ridge, then bombed down the screefield in the avalanche gulch to meet up with the Aylmer Pass trail. We jogged for a few kilometers until Jordan caught a toe and went down hard. He tumbled into the bushes and was silent. I asked if he was okay. Not really, he said. His tooth was embedded in his lip and blood was pouring down his chin.

We jogged for a few kilometers until Jordan caught a toe and went down hard. He tumbled into the bushes and was silent. I asked if he was okay. Not really, he said. His tooth was embedded in his lip and blood was pouring down his chin. Jordan removed his tooth from his lip. Chris cracked open a first-aid kit and we applied pressure to stop the bleeding. Jordan’s teeth seemed to be okay, and he’d probably need a couple stitches, but it became apparent after awhile that he might have a concussion.

Jordan removed his tooth from his lip. Chris cracked open a first-aid kit and we applied pressure to stop the bleeding. Jordan’s teeth seemed to be okay, and he’d probably need a couple stitches, but it became apparent after awhile that he might have a concussion. In his semi-concussed state, Jordan repetitively asked (among other questions) whether I was planning to swim again. The day was supposed to have two swims, and as the model for the “Picnic” goes, you bike, then swim, then climb, then do it all in reverse.

In his semi-concussed state, Jordan repetitively asked (among other questions) whether I was planning to swim again. The day was supposed to have two swims, and as the model for the “Picnic” goes, you bike, then swim, then climb, then do it all in reverse. We reached the parking lot around 9h14m. Chris and Jordan loaded their bikes into Chris’ car and headed down to get Jordan some stitches. I saddled up on the roadie for the downhill rip into town.

We reached the parking lot around 9h14m. Chris and Jordan loaded their bikes into Chris’ car and headed down to get Jordan some stitches. I saddled up on the roadie for the downhill rip into town. Splits:

Splits: When I got back from Italy in July, I started running in the mountains like I’d forgotten all about the saga of injuries I’d been dealing with most of the year, and pretty much made the same mistakes I made back in May. I ran the Cory-Edith loop with friends, then tagged Edith a couple days later, then biked and hiked to Egypt Lake a few days after that. I stopped doing physio exercises partway through my trip to Europe — the dorm at Rifugio Lagazuoi was the last time I used a resistance band — so it was little wonder when my tib-post/plantar issues flared up after getting back from Egypt Lake.

When I got back from Italy in July, I started running in the mountains like I’d forgotten all about the saga of injuries I’d been dealing with most of the year, and pretty much made the same mistakes I made back in May. I ran the Cory-Edith loop with friends, then tagged Edith a couple days later, then biked and hiked to Egypt Lake a few days after that. I stopped doing physio exercises partway through my trip to Europe — the dorm at Rifugio Lagazuoi was the last time I used a resistance band — so it was little wonder when my tib-post/plantar issues flared up after getting back from Egypt Lake. One upside to my inability to run has been embracing the bike more wholeheartedly. Last fall I completed an “

One upside to my inability to run has been embracing the bike more wholeheartedly. Last fall I completed an “ Luckily, this summer wasn’t solely restricted to riding my bike, and by mid-August my foot was healthy enough to fathom the prospect of trotting up and down eleveners and stuff:

Luckily, this summer wasn’t solely restricted to riding my bike, and by mid-August my foot was healthy enough to fathom the prospect of trotting up and down eleveners and stuff: Jokes about “uphill swimming” were aplenty as our shoes sifted through the fossils beds and we looked for any trilobytes. Eventually we reached the ascent gullies that lead to Atha’s summit ridge: steep, hard-packed, and littered with choss. The scrambling isn’t difficult but managing rockfall is the real hazard. As we all stayed out of each other’s way and were keen to call out falling rocks, we made it to the ridge in no time.

Jokes about “uphill swimming” were aplenty as our shoes sifted through the fossils beds and we looked for any trilobytes. Eventually we reached the ascent gullies that lead to Atha’s summit ridge: steep, hard-packed, and littered with choss. The scrambling isn’t difficult but managing rockfall is the real hazard. As we all stayed out of each other’s way and were keen to call out falling rocks, we made it to the ridge in no time. The grind up the ridge to Silverhorn was less technical than the gullies, but dark clouds were hovering, making me uneasy, and I could sense the altitude was starting to tucker out Glenn.

The grind up the ridge to Silverhorn was less technical than the gullies, but dark clouds were hovering, making me uneasy, and I could sense the altitude was starting to tucker out Glenn. We made it to Silverhorn, Athabasca’s snowy sub-summit, and prepared for the moment of truth: would snow conditions allow us to climb to the summit? This year we were prepared, packing Microspikes, and I had an ice axe, refusing to let any snow climbing stop me. The west side of the ridge leading to the summit was completely bare of snow, allowing us to tread solely on scree. The only detour of any technicality was the need to cross an icy gully by leaping between two rotten, chossy ledges.

We made it to Silverhorn, Athabasca’s snowy sub-summit, and prepared for the moment of truth: would snow conditions allow us to climb to the summit? This year we were prepared, packing Microspikes, and I had an ice axe, refusing to let any snow climbing stop me. The west side of the ridge leading to the summit was completely bare of snow, allowing us to tread solely on scree. The only detour of any technicality was the need to cross an icy gully by leaping between two rotten, chossy ledges. At last we were on top. An elevener bagged. The vendetta was resolved; Athabasca and I were on good terms. I kicked steps up the huge fin of snow that sits atop the summit, gazed out at the sea of mountains, and drove the shaft of my ice axe into the snow triumphantly. Only problem was that the jagged pick of the ice axe was embedded in my leg. Still working on this alpinism thing, I guess.

At last we were on top. An elevener bagged. The vendetta was resolved; Athabasca and I were on good terms. I kicked steps up the huge fin of snow that sits atop the summit, gazed out at the sea of mountains, and drove the shaft of my ice axe into the snow triumphantly. Only problem was that the jagged pick of the ice axe was embedded in my leg. Still working on this alpinism thing, I guess. We hung around for a half-hour soaking up the epicness that surrounded us. The Columbia Icefield is a crazy place, giving the impression of a different epoch in Earth’s history. Though the outlet glaciers have dwindled, it is easy to imagine these immense mountains as humble nunataks protruding from the icecap many eons ago.

We hung around for a half-hour soaking up the epicness that surrounded us. The Columbia Icefield is a crazy place, giving the impression of a different epoch in Earth’s history. Though the outlet glaciers have dwindled, it is easy to imagine these immense mountains as humble nunataks protruding from the icecap many eons ago. Temple Duathlon

Temple Duathlon I left the house at 3:41am and started spinning. The ride went by mostly in the dark which was my wont; not a single car passed me on the 1A until I got to Lake Louise. When I saw the silhouette of Mount Temple, so huge and still so far away, I shuddered and doubts started to creep into my consciousness.