I’m being escorted out of the airport by security who say “no bikes”, even though I just spent over an hour putting mine together outside Starbucks between sips of latte. Now, however, it’s “no bikes” but that’s convenient because it’s time for me to leave the airport and face the whirlwind that is Mexico City.

I’m being escorted out of the airport by security who say “no bikes”, even though I just spent over an hour putting mine together outside Starbucks between sips of latte. Now, however, it’s “no bikes” but that’s convenient because it’s time for me to leave the airport and face the whirlwind that is Mexico City.

We step outside and the first thing I notice is heat, not sounds or smells or traffic or tacos. There is a sun here, and it’s hot compared to the cold, dark place I just came from. I push my bike over to the curb to roll a cigarette. I’m staring into the sun, sweltering, wishing I’d put on shorts before getting kicked out of the airport.

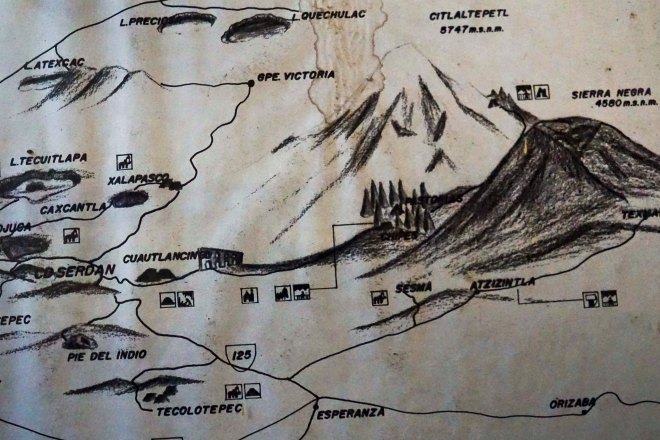

I’ve returned to Mexico in an attempt to link up three of its highest mountains using human power alone, and the capital city is the starting point. Not only that, but I’ve elected to start in the deepest part of the city, the centro zocalo, and fight my way out from there. The urban chaos is part of the adventure.

But before that, I have to reach my hostel in the zocalo, in one piece.

I must be getting close, because there are so many people that I have to get off my bike and walk. It’s Sunday: vendors are out, indigenous Nahuatl dancers are putting on a show, and people of all walks throng about, eating street food and taking pictures of everything.

I must be getting close, because there are so many people that I have to get off my bike and walk. It’s Sunday: vendors are out, indigenous Nahuatl dancers are putting on a show, and people of all walks throng about, eating street food and taking pictures of everything.

With jugs of water and snacks to sustain me over the next few days, I migrate from 7-11 to the massive cathedral across the street that dominates the central square.

It’s no wonder I didn’t latch on to Christianity as a kid, I think as I wander inside. Catholic iconography is scary. I gaze up at the blood and the thorns and the cross and all the ornateness, and shiver. It’s psychedelic, but like an acid trip gone bad.

But the architecture is impressive, the ceilings are high, mass is being performed and the whole experience is powerful. The gravity of what I’ve come to do here wells up inside of me. I’ve spent months planning, fretting, doubting myself, encouraging myself, and ultimately forcing myself to do this. Now here I am, at a church in Mexico City on the eve of my trip, clutching a straw cowboy hat and feeling very emotional.

Birth and death and exorcism and transcendence, all rolled into one.

Day 1 – Mexico City to Amecameca

After breakfast, I make a quick pit-stop to pick up gas for my stove, then circle back to the zocalo to start the trip proper.

Rewind to my first trip to Mexico, two years prior: I’m thinking of the foolhardy but Instagram-worthy idea of renting a motorcycle and riding it around to climb the various peaks. Never mind that I’ve never ridden a motorcycle, let alone in another country — it’s going to look great on the ‘Gram. It’s good that never materialized, for I surely would’ve died in traffic long before ever seeing a mountain in Mexico.

Picture me, selfie-stick style, riding across the open plains on a motorcycle, towards some distant peak — leather jacket and all. Now here I am, doing pretty much the same thing on a bicycle.

Heads up, eyes peeled. Fugazi is blasting in my headphones as I mash at the pedals, darting in and out of lanes and drafting in the wake of colectivos. Traffic isn’t heavy, but it’s fast, and it’s exhilarating to ride around the way most Mexico City drivers do — by not giving a fuck.

Heads up, eyes peeled. Fugazi is blasting in my headphones as I mash at the pedals, darting in and out of lanes and drafting in the wake of colectivos. Traffic isn’t heavy, but it’s fast, and it’s exhilarating to ride around the way most Mexico City drivers do — by not giving a fuck.

See, on my first trip, I learned the rules of the road in Mexico City: do whatever you want, and everyone else simply deals with it.

After a few blocks of high-octane bike karate, everything suddenly stops. I’m being funneled into a tighter and more congested alleyway, which is technically a road, but today it’s a market, so deal with it.

I hop off my bike and try to squeeze through: first past a guy pulling a dolly stacked with teetering crates; then a three-wheeled bicycle just as precariously overloaded. Pedestrians zip every which way and vehicles moored in the chaos idly sit there, resigned to their fate.

“I’m going to make great progress at this rate,” I moan, but in this moment of hesitation, someone half my size with a barrel of horchata twice as big as me has already cut in front, and is off like a bullet and out of sight. I can only shrug: Mexico City rules.

Arriving in Amecameca, I embrace a lukewarm shower and a huge sandwich at the torta shop. Altzomoni Hut is closed, according to the woman at the national park headquarters, but it only puts a minor kink in my plans to climb Iztaccihuatl. The black stormcloud hanging overtop of Izta threatens to pose another.

Arriving in Amecameca, I embrace a lukewarm shower and a huge sandwich at the torta shop. Altzomoni Hut is closed, according to the woman at the national park headquarters, but it only puts a minor kink in my plans to climb Iztaccihuatl. The black stormcloud hanging overtop of Izta threatens to pose another.

I take a bite of my gargantuan sandwich, the cubana, loaded with everything in the sandwich shop. Between the hill that appeared sadistically at the end of the day, and sheer anxiety that’s been consuming me calorically for weeks, God knows there aren’t enough cubanas in the world to make me comfortable with what I’ve taken on here. But at least the crux of the trip is over — I made it out of Mexico City alive.

Day 2 – Amecameca to Paso de Cortes

With only twenty five kilometers ahead of me today, I feel fine to lounge, probing the mysteries contained in my breakfast burrito and the curious sauce in which it is steeped. Those twenty-five kilometers, of course, contain 1200 meters of elevation gain — the height of most mountains around Banff. So I’ll be climbing a mountain on my bike today, just to get to the base of a real one.

I roll out of Amecameca and start granny-gearing towards the pass. The scene seems quintessentially Mexican: mountains, cornfields, donkeys tied up by the side of the road, and dudes siesta-ing around a pickup truck even though it’s only, like, ten in the morning. This is something I’d looked forward to seeing from my open-air cockpit, at this snail’s pace, not the back seat of a taxi whipping along at mach speed.

The route turns left and with it comes a sharp increase in steepness, the concerted climb to the pass. I pedal past the last village, maintaining some measure of dignity, then hop off and resort to pushing my bike up the hill. Still, small roadside tiendas beckon me to come sample whatever they’re cooking.

The road is paved and meanders in wide switchbacks, granting increasingly wider views of the valley below. The foreground scenery is also noticeably green and verdant. The going is tough but not impossible, and my performance is enhanced by a warm Fanta from one of the spartan snack shacks along the way.

The road is paved and meanders in wide switchbacks, granting increasingly wider views of the valley below. The foreground scenery is also noticeably green and verdant. The going is tough but not impossible, and my performance is enhanced by a warm Fanta from one of the spartan snack shacks along the way.

Rain starts with a sputter, then like someone’s turned on a tap. I look at my watch, it’s three PM: precisely as forecasted. Lucky for me, I’ve happened upon a vacant shack at just this moment, beneath which to shelter from the elements. If you don’t like the weather in the mountains, just wait five minutes, I say.

One hour later, the elements show no sign of stopping. I’m bundled in all my layers. I already drank one Nescafe, but I’m starting to shiver, and thinking about brewing up another. But in my periphery, I see movement.

One hour later, the elements show no sign of stopping. I’m bundled in all my layers. I already drank one Nescafe, but I’m starting to shiver, and thinking about brewing up another. But in my periphery, I see movement.

A man is walking up the road in a t-shirt and shorts, obviously undeterred by the drenching rain. He walks over to my shack and we make conversation that quickly surpassesmy limited grasp of Spanish. He is, as far as I can tell, a man with nothing walking somewhere.

He opens a plastic bag and produces an enormous mushroom, presumably plucked from the forest. He shoves it my way, seeming to suggest I should eat some. Now I’m pretty open-minded when it comes to foreign food, but I don’t wish to be poisoned, or have a hallucinogenic experience right now, no gracias.

He shrugs and devours almost the whole huge mushroom in one big bite before sticking it back in his sack. Next is the pelt of some small animal which he’s pulling out to show me. Cool, right? But then he demonstrates his real intent: he’s going to wear it on his ballcap, Davy Crockett-style. But for the moment, it just looks grotesque.

It’s almost dark, and the red light is flashing furiously on the back of my bike. The pass has got to be close. I leapfrogged in front of Davy Crockett and he’s following somewhere behind me. My mind is reeling: If he likes to skin animals, maybe he wants to skin a gringo… So I’m pushing my bike real fast up this hill now.

It’s almost dark, and the red light is flashing furiously on the back of my bike. The pass has got to be close. I leapfrogged in front of Davy Crockett and he’s following somewhere behind me. My mind is reeling: If he likes to skin animals, maybe he wants to skin a gringo… So I’m pushing my bike real fast up this hill now.

At last, I get to Paso de Cortes and go into the park office to try to find a place to sleep. It’s obvious I’m not going to reach La Joya before dark, and I don’t have ambitions to get there tonight anyhow. I’m pooped. They say I can camp right here, and point towards some trees where there are apparently campsites.

A little doggie accompanys me. It’s cold, and I’m rushing to set up the tent and boil a package of ramen noodles — habanero flavor I discover, upon taking the first sip. I need to recover at least 1000 calories, and they all sear on the way down.

A little doggie accompanys me. It’s cold, and I’m rushing to set up the tent and boil a package of ramen noodles — habanero flavor I discover, upon taking the first sip. I need to recover at least 1000 calories, and they all sear on the way down.

I lay down in my sleeping bag and try to identify the sound I’m hearing, like distant thunder. It could be a number of things: the sound could be fiery lava-balls ejected from the top of Popocatepetl. Or the ubiquitous use of dynamite for mining, which across Mexico sounds like the continuous refrain of artillery fire.

In this case, it’s actually thunder, and as it rises in intensity, I wonder what sort of scene I’ll wake up to in the morning.

Day 3 – Paso de Cortes to Cholula

I’m gripping the brakes, descending down a washboard dirt road for at least the last hour. My bags are threatened of being shaken off my bike, and I readjust my helmet which has sunken over my eyes, in an effort to squint through the fog.

I’m gripping the brakes, descending down a washboard dirt road for at least the last hour. My bags are threatened of being shaken off my bike, and I readjust my helmet which has sunken over my eyes, in an effort to squint through the fog.

I woke up at Paso de Cortes in the clouds and wrote off an ascent of Izta. There didn’t seem much hope of clear visibility on a snow-covered mountain, plus I was a bit frazzled from the day before. I wanted warm eggs and coffee, but breakfast consisted of a smoke and thimbleful of Nescafe, tasting vaguely of habanero seasoning, while standing in the damp Scottish pall.

I should be in Cholula in no time, I say, expecting a thousand-meter descent on smooth pavement to deliver me to a steaming plate of eggs and coffee. But here I am, white-knuckled and weaving between massive rocks on a road that is, “at least sometimes passable by 4-wheel-drive vehicles,” as per the most cursory of sources on the Internet. Trip research fail.

I should be in Cholula in no time, I say, expecting a thousand-meter descent on smooth pavement to deliver me to a steaming plate of eggs and coffee. But here I am, white-knuckled and weaving between massive rocks on a road that is, “at least sometimes passable by 4-wheel-drive vehicles,” as per the most cursory of sources on the Internet. Trip research fail.

Eventually I’m back on blessed pavement and pushing my bike through a small town with the ambiance of a huge carnival, looking for someplace to eat. I sit down at one establishment and coffee is doled out of a huge vat on the stove, then microwaved until molten. Coffee Mate is added to produce a potently noxious elixir. Tacos are consumed by the plateful as kids zip underneath tables and marching bands contribute to the relaxing atmosphere.

Day 6 – La Malinche

Finally, a mountain. Just a mountain. I’m not fighting my way out of a city, or pushing my bike up endless switchbacks, or lost on some God-forsaken backroad. I’m simply walking up a mountain, an easy one, and one I’ve walked up before: La Malinche.

Finally, a mountain. Just a mountain. I’m not fighting my way out of a city, or pushing my bike up endless switchbacks, or lost on some God-forsaken backroad. I’m simply walking up a mountain, an easy one, and one I’ve walked up before: La Malinche.

For the first time, I actually feel comfortable on this trip, but clearly other people around me do not. Groups are halted on the steep, sandy embankment like frozen congo lines, struggling to catch their breath. One guy is throwing up on the side of the trail, though we’re not even out of the trees yet.

I crest the ridge as tendrils of cloud are uplifted by the mountain, standing alone in the landscape for a hundred kilometers in every direction. Arriving at the summit, I face a veritable party dominated by… Germans? But the views from this “easy” mountain have me transfixed. You actually can’t see much because of the clouds, but through brief glimpses of crumbling rock in the caldera, I’m given a vision of heaven and hell.

I crest the ridge as tendrils of cloud are uplifted by the mountain, standing alone in the landscape for a hundred kilometers in every direction. Arriving at the summit, I face a veritable party dominated by… Germans? But the views from this “easy” mountain have me transfixed. You actually can’t see much because of the clouds, but through brief glimpses of crumbling rock in the caldera, I’m given a vision of heaven and hell.

Day 7 – La Malinche to Ciudad Serdán

It’s early, I’ve got a hundred kilometers to get to Ciudad Serdán, and already have two complications: a swollen ankle from miscalculating my descent while hurtling down La Malinche at Kilian Jornet pace, and a headache from drinking a few too many with Marco and Pepe ’round the campfire last night. I bundle up and prepare for a chilly descent into Huamantla in search of food and coffee.

After breakfast, the day begins innocuously. I’m riding mostly downhill, against the grain of some kind of festive parade involving decorated trucks, combined with a relay race with bikes and on foot. The vista opens up as I ride across the wide salt lake, Totolcingo, mashing the big ring across the flats towards the snowcapped summit of Orizaba.

With ninety degrees’ change of direction comes a 180° reversal of luck. I’ve hit a headwind that batters every effort to make forward progress, and still have 40 kilometers to go. The road’s definitely no longer downhill. It looks flat, but it feels like I’m riding up a mountain.

With ninety degrees’ change of direction comes a 180° reversal of luck. I’ve hit a headwind that batters every effort to make forward progress, and still have 40 kilometers to go. The road’s definitely no longer downhill. It looks flat, but it feels like I’m riding up a mountain.

After a long, bonky crusade against the wind and exhaustion, I arrive at the Hotel Montecarlo, a true refuge for the mountaineer in this part of Mexico, compared to the crude shipping crates which pass for huts up high. It feels surreal to be here again but with my bike as means of transport.

After a long, bonky crusade against the wind and exhaustion, I arrive at the Hotel Montecarlo, a true refuge for the mountaineer in this part of Mexico, compared to the crude shipping crates which pass for huts up high. It feels surreal to be here again but with my bike as means of transport.

It’s my second time in Serdán, so I know all the good torta shops. I plop down at my favourite one, order una cubana y cerveza, demolish both, and order another round. My legs are in pain from the day’s effort, and any attempt to move them results in protests of agony.

With good weather coming on Orizaba three days hence, I decide a rest day is in order. A glorious day to wake up late, linger over espressos, wander the streets and see the sights, eat tacos, take pictures and — best of all — not ride my bike!

Day 9 – Up to Orizaba

After a rejuvenating day doing nothing, I’m riding down the street in Ciudad Serdán on my fully loaded bike, en route to my final mountain. But one coffee wasn’t enough, so I’m pulling over to nurse another. Besides, I’ve got an easy day today: 25kms and 1500m of elevation gain — been there, done that — and climbing Orizaba itself doesn’t faze me. I’m finally smelling the barn.

Leaving Serdán, the route is invariably uphill; sometimes riding, sometimes pushing, but I’m comfortable with the process now, doing whatever feels natural. I’m chugging along beside picturesque fields, with flocks of sheep and German Shepherds guarding them, and kids that should be in school but are out in the fresh air pretending to do farm work. For once on this trip, everything sorta feels right.

I poke around the last village in hope of a taco shop or something to satiate my desire for lunch, and realize there’s little more here than a bunch of houses. The sound of artillery fire is atrocious, and my entire body is punctuated by a shockwave when one unexpectedly goes off.

I poke around the last village in hope of a taco shop or something to satiate my desire for lunch, and realize there’s little more here than a bunch of houses. The sound of artillery fire is atrocious, and my entire body is punctuated by a shockwave when one unexpectedly goes off.

Suddenly I get to the end of the village and there is nothing, just some brush and maybe a dry riverbed. I stare down at my GPS, then at the jumble of rocks and dirt, in confusion. Fortunately there are two boys there, having a conversation about whatever ten and twelve-year-olds talk about in Mexico.

“Pico de Orizaba?” I ask, pointing in the general direction of the mountain.

“Pico de Orizaba?” I ask, pointing in the general direction of the mountain.

“Si,” says the older boy, dressed in neat schoolclothes.

“Donde es el camino?” I ask, and the boy proceeds to provide a lengthy discourse upon the local geography, of which I comprehend almost nothing. The gist is: you can go all the way around the long way, otherwise this is it.

He’s not very old, but despite the language barrier, the boy’s breadth of knowledge indicates that he knows what he’s talking about. Before delving onto the dirt path, I ask, one last time, if this is the right way. They assure me it is, but I can’t be certain they aren’t just fucking with a clueless gringo.

“You said you wanted to suffer!” I yell, in between expletives and gasping for oxygen. I can’t deny that I did. And while this is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done, I’m conscious that this is exactly what I asked for.

“You said you wanted to suffer!” I yell, in between expletives and gasping for oxygen. I can’t deny that I did. And while this is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done, I’m conscious that this is exactly what I asked for.

I’ve been pushing my bike up this “road” for the past two hours, the same road Google says you can drive up in a car. Ha ha, bullshit. The rocks are sliding under my feet as I push my bike two, three steps upwards before clenching the brakes to stop it from rolling backwards on me. I collapse over the bike in an effort to catch my breath — but I’m not making progress doing nothing, so off I go on another series of fruitless steps.

Altitude I’m cool with. Endurance, sure. But this is like some kind of Herculean punishment, like pushing a rock up a mountain that continually rolls back down.

Altitude I’m cool with. Endurance, sure. But this is like some kind of Herculean punishment, like pushing a rock up a mountain that continually rolls back down.

My watch reads 1500 meters but I’m still climbing, and although the grade is less steep, the air is thinner and it’s not any easier. I break out of the trees and there is blue sky. But a rumbling below betrays some sort of motorized vehicle — in this case, a farm tractor, hauling a contingent of climbers intent on bagging Orizaba.

Our arrival to the pass is a tie, and I even manage to ride the last few meters, but I don’t have the energy to push my bike up to the main climbers’ hut 500 meters higher. I’ll have to camp here and climb Orizaba in a single push tomorrow morning.

Day 10 – Pico de Orizaba

I sensed it, before it happened. I heard the truck pull up, the voices, then bang, bang, bang! They were kicking in the door and firing questions at me in Spanish which I didn’t understand.

“No entiendo,” I say. I don’t have the mental capacity to try and muster a response to the questions they’re asking. It’s three in the morning and I was just asleep in my sleeping bag before these assholes showed up to offer me a wake up call.

I found a place to sleep in the lower albergue, a stone building at the pass divided into two rooms, the inside of which could easily double for a Hollywood dungeon or torture chamber. I heard them examining the adjacent room. Then, “Hey, what’s in here?” Bang, bang, bang!

“No entiendo,” I repeat. They motion that I should go back to sleep. But I have to get up and climb Orizaba anyway.

A half-hour later, I’m out the door. “Maybe I’ll get a headstart on the rest of the climbers,” I say, but can already see a line of twinkling dots scaling what I assume is the Ruta Sur.

A half-hour later, I’m out the door. “Maybe I’ll get a headstart on the rest of the climbers,” I say, but can already see a line of twinkling dots scaling what I assume is the Ruta Sur.

Having done this once before, I have the ascent dialed. I traverse off the loose scree early, over to the boulders, and make quick progress using my hands and feet. One climber, a young guy, is coming down, disoriented, with the light of his cellphone to guide him. I point him in the direction of the rifugio and continue on my way.

I reach the wall of steep, loose scree that is mainly a nuisance, but a risk to one’s life in the most inane way: rocks are easily dislodged here and this final stretch is not only slow due to altitude and terrain, but also a shooting gallery of debris kicked down by parties up above.

I reach the wall of steep, loose scree that is mainly a nuisance, but a risk to one’s life in the most inane way: rocks are easily dislodged here and this final stretch is not only slow due to altitude and terrain, but also a shooting gallery of debris kicked down by parties up above.

I don my bike helmet accordingly, and claw my way to the summit of Orizaba, exasperated breath by exasperated breath.

Back at the dungeon, six hours later, I’m being interrogated by two boys who want to know everything about my bike, where I came from, and where I’m going next.

Back at the dungeon, six hours later, I’m being interrogated by two boys who want to know everything about my bike, where I came from, and where I’m going next.

I’m sitting on the stone wall making soup and packing my bike. A little girl is staring at me. This family is out for a day trip, enjoying what fresh air is to be found at four thousand meters above sea level. After soup, I’m rolling up a smoke, and the father comes over to ask, I assume, to have one. I hand him the tobacco.

“Roll two,” I say. But he just wants a few papers so he can roll a joint.

With the help of the boys, I’m done packing my bike and ready to go. The father is leaned up under the shade of a tree, sucking his ganja. I saunter over and ask for “uno puff” and inhale the filthy mota as deeply into my lungs as I can. I walk back to my bike, get on, and say adios. They all say adios to me.

I crank on the drivetrain and, in a cloud of volcanic dust, I’m gone.

After climbing Orizaba, I’ve earned the easy part: a three kilometer descent on my bike. Putting that in perspective, it’s a big drop. Like cycling down two Banff mountains stacked on top of each other, no pedaling required.

After climbing Orizaba, I’ve earned the easy part: a three kilometer descent on my bike. Putting that in perspective, it’s a big drop. Like cycling down two Banff mountains stacked on top of each other, no pedaling required.

I lose vert like nobody’s business, bombing though farming villages, alongside herds of sheep, shepherds nodding as I pass. I cross into the watershed east of Orizaba where wet air from the Atlantic slams into the Sierra Madre and the vegetation appears immediately more lush. I’m going thirty, forty, fifty kilometers an hour, passing trucks on the highway creeping cautiously down the endless decline.

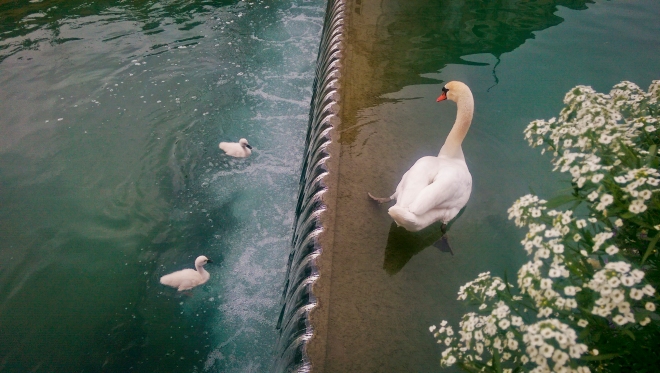

I reach the oasis town of Orizaba, where an intoxicatingly romantic waterway runs through, lined with exotic pets: a panther paces in its cage; another is as dull as a sloth. I don’t care to see the bears. The hills take on the hue of sunset as I walk back beside the river, dragging my hand along the damp and mossy wall.

Day 11 – Orizaba to Soledad de Doblado

I stumble into the taco shop like some sort of zombie and plunk down in the plastic chair. I order two quesadillas, Fanta and lots of water. Beads of sweat have blistered on my arms, and there’s a streak of black dirt across my face. I didn’t expect today to be so hot, baking on the side of the road, in the middle of nowhere, staring at the last sip of water slosh around the bottom of my Nalgene bottle.

It was my plan to reach Veracruz today but it’s late, and I still have forty kilometers to go. I don’t want to bunker down in this desolate village, so close to being done, but fear I won’t make it to Veracruz until after sundown. Riding my bike after dark in Mexico is something I’m not willing to do.

But there’s a hotel here in Soledad de Doblado, I’m told, and I’m racing through the streets behind an ATV that’s offered to take me there. I go up the steps of Hotel Jardin and an old lady looks at me contemptfully. With a wrinkled nose she takes my 200 pesos and shows me to a dilapidated room. The bed is sunken in the middle and insects scurry when I pull back the sheets. Faded Toy Story curtains round out the decor.

But there’s a hotel here in Soledad de Doblado, I’m told, and I’m racing through the streets behind an ATV that’s offered to take me there. I go up the steps of Hotel Jardin and an old lady looks at me contemptfully. With a wrinkled nose she takes my 200 pesos and shows me to a dilapidated room. The bed is sunken in the middle and insects scurry when I pull back the sheets. Faded Toy Story curtains round out the decor.

The shower’s hot, however, and I understand why the woman looked at me funny when I look in the mirror and see the black streak across my face.

Day 12 – To Veracruz

Lying in my sagging bed, I’m awakened by gale-force wind shaking the entire building. The windows chatter, something on the roof is clanging away, and that broken sign that made this place seem like even more of a shithole, it makes perfect sense now.

I peer out the window at the flapping flags strung across the street and do some geographical arithmetic: I’m fucked. Today is the last day of my trip and supposed to be the easiest one, but it’s no surprise I’ve been tossed this curveball as if to say, “the sufferfiesta’s not over yet.”

Legs madly spinning into a wall of resistance, I’m growling through clenched teeth. I desperately look at the altitude on my watch, expecting to see it drop towards zero, but the number is going up, not down. Today’s supposed to be a descent to sea level — why am I still climbing then?

Legs madly spinning into a wall of resistance, I’m growling through clenched teeth. I desperately look at the altitude on my watch, expecting to see it drop towards zero, but the number is going up, not down. Today’s supposed to be a descent to sea level — why am I still climbing then?

In the industrial outskirts of Veracruz, three lanes of gridlocked transport trucks provide solace from the wind. I’m run off the shoulder by one but don’t care, I’m ripping through the dirt and passing the offender. Then I’m in the suburbs, racing towards my goal. Someone steps off the curb while staring at their cellphone. I slam on the brakes and skid around, leaving them petrified in my wake.

I don’t care about any of this. I’m on a mission to get to the ocean. And while the city of Veracruz may hold some casual interest, I’m too focused to care.

I come around the corner of a pastel-colored hotel and see the blue expanse. I’m not sure if there is relief, or just shellshock. I cross the street and there’s a sense of, “Wow, I did it, I’m really here”, as I ride along the waterfront but, honestly, I just feel numb.

I come around the corner of a pastel-colored hotel and see the blue expanse. I’m not sure if there is relief, or just shellshock. I cross the street and there’s a sense of, “Wow, I did it, I’m really here”, as I ride along the waterfront but, honestly, I just feel numb.

I lean my bike against a chair that’s been carved out of stone, looking out over the ocean. The wind still howls and threatens to blow my bike off this solid support. I gaze at the water as the waves crash and the wind blows so loud it’s impossible to think. But I’m not thinking about anything. After a few minutes, I take a couple pictures and scan the oceanside: where’s McDonalds?

Day 14 – Home

“I’m sorry, Mr. Amaral, but we can’t transport your box.”

I’m very civil when they explain about the holiday baggage embargo. Other people might explode like there’s dynamite strapped to their chest. In Veracruz, I’d procured a cardboard box for my bike, loaded it with the accoutrements, purchased a flight home, and sat down contentedly to a seafood dinner. Now the airline’s saying no bueno.

The ticket is refunded and I drag my box over to the next desk. “Cargo,” says the agent and directs me to a building across the parking lot. I lug the box across the parking lot — as arduous as pushing my bike up to Orizaba — expecting to get the problem sorted. But it’s Sunday and the cargo division is closed.

I slump on the curb and roll my last pinch of tobacco. In the past, I’d have a meltdown right now, but I’ve taken so many punches on this trip, I can only laugh.

As I sit beside my giant box repeating the F-word, my guardian angel appears on a white moped. I assault him with questions, assuming he works in cargo. He is very kind with my desperation. He’s actually a ticket agent and suggests we go back to the airport. He wants to know exactly what happened and leaves to speak with his colleagues. After a couple minutes, he comes back and says, “Mr. Amaral, we can transport your box.”

As I sit beside my giant box repeating the F-word, my guardian angel appears on a white moped. I assault him with questions, assuming he works in cargo. He is very kind with my desperation. He’s actually a ticket agent and suggests we go back to the airport. He wants to know exactly what happened and leaves to speak with his colleagues. After a couple minutes, he comes back and says, “Mr. Amaral, we can transport your box.”

Another adventure complete. I lean back in my seat and am catapulted back to Mexico City. What took me two weeks by bicycle, takes thirty minutes by airplane. But as I stare out the window at Pico de Orizaba, I don’t regret taking the slow, painful, excruciatingly rewarding way to get there.

Summary:

03/12/18 Mexico City to Amecameca – 60km | 329m ↑

04/12/18 Amecameca to Paso de Cortes – 25km | 1249m ↑

05/12/18 Paso de Cortes to Cholula – 37km | 1543m ↓

06/12/18 Cholula to Tlaxala – 45km | 465m ↑

07/12/18 Tlaxala to IMSS La Malinzi – 22km | 854m ↑

08/12/18 La Malinche (4460m) – ~1500m ↑

09/12/18 IMSS La Malinzi to Ciudad Serdan – 103km | 516m ↑

10/12/18 Rest day in Serdan

11/12/18 Ciudad Serdan to Orizaba/S. Negra col – 24km | 1536m ↑

12/12/18 Pico de Orizaba (5636m) + to town of Orizaba – 66km | 1300m ↓

13/12/18 Orizaba to Soledad de Doblado – 94km | 472m ↑

14/12/18 Soledad de Doblado to Veracruz – 43km | 394m ↑

▲